By Dhani Irwanto, 26 September 2015

Contents

Background

Trading with Southeast Asia

Early World Mapping

Ptolemy’s World Map

Definitions of India

The Island of Taprobana

Kalimantan Hypothesis for Taprobana

– World Map Development

– Geographic Conditions of Taprobana

– Ancient Maps of Kalimantan

– Geographic Names Identification

Taprobrana and The Search for Atlantis

Trading with Southeast Asia

Early World Mapping

Ptolemy’s World Map

Definitions of India

The Island of Taprobana

Kalimantan Hypothesis for Taprobana

– World Map Development

– Geographic Conditions of Taprobana

– Ancient Maps of Kalimantan

– Geographic Names Identification

Taprobrana and The Search for Atlantis

Background

Taprobana (Ancient Greek: Ταπροβανᾶ) or Taprobane (Ταπροβανῆ) was the historical name for an island in the Indian Ocean.

Onesicritus (ca 360 BC – ca290

BC) was the first author that mentioned the island of Taprobana. The name was also reported to Europeans by the Greek

geographer Megasthenes around 290 BC, and was later adopted by Ptolemy in his own geographical treatise to identify a

relatively large island south of continental Asia. Though the exact place to which the name referred remains uncertain, some

scholars consider it to be a wild misinterpretation of any one of several islands, including Sumatera and Sri Lanka.

The island entered European consciousness during the conquests of Alexander the Great. Alexander’s admirals Nearchus and

Onesicritus described Taprobana in their reports to their king. Nearchus sailed around the southern tip of India, describing

the smells of cinnamon that wafted from the fabulous island he passed along the way. Megasthenes, Seleucus’s ambassador to

the court of Chandragupta Maurya, fleshed the place out a bit more. Several Roman cartographers and historians wrestled with

the size, shape, and position of Taprobana before Claudius Ptolemy described an immense “Taprobana” in his Geographia, written about AD 150, six times the size of the Indian subcontinent and

straddling the equator.

After the fall of Rome, European geography entered a Dark Age more profound than that of most other disciplines. Like

many ancient books and scholarly works, especially those housed at the Library at Alexandria, the work of Ptolemy was lost

for over a thousand years in Western scholarship. At the end of the 1400s, after Renaissance scholars studying the writings

of the Muslim scholars who had preserved much of the classical knowledge that had been lost to the West, his work was

rediscovered and translated into Latin, a more commonly used language of Western scholars at the time. Geographia became popular once again and more than 40 editions were printed.

In his work Geographia, Ptolemy described and compiled all knowledge about the

world’s geography in the Roman Empire of the 2nd century. A substantial undertaking in scholarship of the day, Geographia was written in eight volumes. The first part discusses the

problems of projections, that is, representing spherical item such as the earth on a flat sheet of paper. The second part

included seven volumes and was composed entirely of atlas.

One problem modern historians have encountered when researching Ptolemy’s work is that his works were all copied by hand and

redistributed. Many of his maps were not redrawn when copies were made and most copies known to exist today do not include

his drawings; rather, the books include maps made many centuries later based on his descriptions or are missing maps

altogether. One such source that points out this problem is an Arabian scholar by the name of al-Mas’udi who wrote around AD

956 that Ptolemy’sGeographia mentioned a colored map with more than 4,530

cities plotted and over 200 mountains. In Ptolemy’s world map he identifies many modern geographic areas including Taprobana

and Aurea Chersoneus.

This has been the primary subject of debate over Taprobana. Each succeeding generation has read vague descriptions of the

island left by their predecessors, and wrangled over what their predecessors really meant. 18th and 19th century scholars

began to think that Ptolemy confused Sri Lanka with Sumatera, or even the lower peninsula of India. In the end, it is

impossible to assign a single place with all of the qualities that have been labeled with the name “Taprobana” over the

ages.

The name Taprobana had been applied to Sumatera from the fifteenth century onwards, after a misunderstanding by the Italian

traveller Nicolo di Conti. Conti was the first European traveler who distinguished Sri Lanka from Taprobana and identified

the latter as Sumatera, which it will be noted, athwart the equator. Subsequent geographers, historians, cosmographers and

thinkers alike became engaged in a controversy over its proper identification. Considerable confusion began to exist as to

whether Sri Lanka or Sumatera was the island of Taprobana and depicted in the Hereford, Ebstrof, Catalan Atlas’ Mappaemundi and on Fra Mauro’s Planisphere and Martin Behaim’sGlobe. The maps such as “Cantino”,

“Caverio” and “Contarini” have misled the contemporary viewers who in their turn transmitted this confusion either through

implicitly casual discussions or even deliberately explicit instructions to mapmakers who in their turn propagated it just

as naively and with the same degree of intelligence as their informants through the documents they were producing for their

immediate users.

The peculiar geographical vicissitudes of Taprobana drew the attention of leading figures from western history, Ramusio,

Gossellin, Kant, and Cassini who concerned with the dilemma, attempted to resolve the question of Taprobana’s identification

with countries ranging from Sumatera to Madagascar. Venetian geographer, historian and humanist Ramusio relying on an

account of an anonymous Portuguese and based on geographical and astronomical data sought to reconcile the location and

dimensions of Sumatera with the position and size of the island that Iambulus the Greek merchant claimed to have discovered.

The aim of his argument thereby was to determine that this island was precisely the Taprobana of the classical

authors.

Sebastian Munster’s map of Taprobana drawn in 1580 carries the German title,Sumatera Ein

Grosser Insel, (“Sumatera, a large island”). The old debate was settled earlier in favor of Sri Lanka, but the more

recent display of Munster’s map with its title has reignited the debate. Munster’s map was “a fine example” of the

difficulties Renaissance map makers had in placing the continents of the world. It showed the cartographic confusion that

Europeans had trying to understand the geography of Asia.

What still baffles everyone is the exaggerated size of Taprobana if Ptolemy really meant the isle to represent present day

Sri Lanka. In contrast, the sub-continent of India which is shown in the map is far smaller in dimensions. It was true that

Sri Lanka by Ptolemy’s time was a well-known island as it was centrally situated in the Indian Ocean but India and her

products were equally known from the pre-Christian era, starting with the Persian occupation of territory up to the river

Sind and Alexander’s conquests following that as well as through sea-borne trade.

On the contrary, Taprobana, despite its sheer size, was assigned by Ptolemy with trade in elephants and golden spices. Both

Sri Lanka and Sumatera were known for these two commodities, and the latter more so for spices but it is Sri Lanka which had

better historical record for elephants. The intelligence displayed by Sri Lankan elephants and easier transport across the

Indian continent perhaps, accounted for preference for them. Sri Lankan elephants began to be exploited in a big way only

after the East African resources dwindled.

Trading with Southeast Asia

Under the Mongol Empire’s hegemony over Asia (the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol peace), Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage, the Silk Road to India

(the Indies, a far larger region than modern India) and China, which were sources of valuable goods such as spices and

silk.

In the early centuries AD, Indians and Westerners called Southeast Asia the “Golden Khersonese”, the “Land of Gold”, and it

was not long thereafter that the region became known for its pepper and the products of its rainforests, first aromatic

woods and resins, and then the finest and rarest of spices. From the seventh to the tenth centuries Arabs and Chinese

thought of Southeast Asia’s gold, as well as the spices that created it; by the fifteenth century sailors from ports on the

Atlantic, at the opposite side of the hemisphere, would sail into unknown oceans in order to find these Spice Islands. They

all knew that Southeast Asia was the spice capital of the world. From roughly 1000 AD until the nineteenth-century

‘industrial age’, all world trade was more or less governed by the ebb and flow of spices in and out of Southeast

Asia.

Throughout these centuries the region and its products never lost their siren quality. Palm trees, gentle surf, wide

beaches, steep mountain slopes covered with lush vegetation, birds and flowers of brilliant colors, as well as orange and

golden tropical sunsets have enchanted its visitors as well as its own people through the ages. Indeed, it is said that when

in the last years of the sixteenth century the first Dutch ship arrived at one of the islands of the Indonesian archipelago,

the entire crew jumped ship, and it took their captain two years to gather them for the return trip to Holland.

In the international trading by land and water several major empires were involved. At the western end of the caravan and

sea routes (the famous Silk Roads) was the Roman Empire, which at the time included the countries around the Mediterranean,

Egypt, the Levant and Arabia. From there the trade routes ran east through the kingdoms of the Parthians and the Kushans in

Central Asia and northern India, through the land of the Shaka (Indo-Scythians) and Shatavahana in northern and central

India, to the South Indian kingdoms of the Cheras, Pandyas and Cholas and, continuing via Sri Lanka and the Bay of Bengal,

to Funan in present-day South Vietnam and to China, at the eastern end of the Silk Roads. The Chinese Han dynasty traded

indirectly with Rome, be it on the caravan routes that led through Central Asia to India, the Persian Gulf and finally to

the eastern Mediterranean, be it across the oceans, from the South China Sea, across the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the

Arabian Sea and the Red Sea as far as Alexandria and Rome. The Southeast Asian archipelago with its medicines, spices and

aromatic substances, with precious timbers and tortoise shell was an important link in this far-reaching trade network,

interconnecting continents.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became much more difficult and

dangerous. Portuguese navigators tried to find a sea way to Asia. In 1470 the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo

Toscanelli suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal that sailing west would be a quicker way to reach the Spice Islands,

Cathay (China) and Cipangu (Japan) than the route round Africa. Afonso rejected his proposal. Portuguese explorers, under

the leadership of King John II, then developed a passage to Asia by sailing around Africa. Major progress in this quest was

achieved in 1488, when Bartolomeu Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope, in what is now South Africa. Meanwhile, in the 1480s,

the Columbus brothers had picked up Toscanelli’s suggestion and proposed a plan to reach the Indies (then construed roughly

as all of south and east Asia) by sailing west across the “Ocean Sea”, ie the Atlantic. During his first voyage in 1492, instead of arriving at Japan as he had intended, Columbus

reached the New World, landing on an island in the Bahamas archipelago that he named “San Salvador”. Over the course of

three more voyages, Columbus visited the Greater and Lesser Antilles, as well as the Caribbean coast of Venezuela and

Central America, claiming all of it for the Crown of Castile.

Portugal was the first European power to establish a bridgehead on the lucrative maritime Southeast Asia trade route, with

the conquest of the Sultanate of Malaka in 1511. The Netherlands and Spain followed and soon superseded Portugal as the main

European powers in the region. In 1599, Spain began to colonize the Philippines. In 1619, acting through the Dutch East

India Company, the Dutch took the city of Sunda Kelapa, renamed it Batavia (now Jakarta) as a base for trading and expansion

into the other parts of Java and the surrounding territory. In 1641, the Dutch took Malaka from the Portuguese. Economic

opportunities attracted Overseas Chinese to the region in great numbers. In 1775, the Lanfang Republic, possibly the first

republic in the region, was established in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, as a tributary state of the Qing Empire; the republic

lasted until 1884, when it fell under Dutch occupation as Qing influence waned.

Englishmen of the United Kingdom, in the guise of the Honorable East India Company led by Josiah Child, had little interest

or impact in the region, and were effectively expelled following the Siam-England war in 1687. Britain, in the guise of the

British East India Company, turned their attention to the Bay of Bengal following the Peace with France and Spain in 1783.

During the conflicts, Britain had struggled for naval superiority with the French, and the need of good harbors became

evident. Penang Island had been brought to the attention of the Government of India by Francis Light. In 1786 a settlement

was formed under the administration of Sir John Macpherson, which formally began British expansion into the Malay States of

Southeast Asia.

The British also temporarily possessed Dutch territories during the Napoleonic Wars; and Spanish areas in the Seven Years’

War. In 1819, Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a key trading post for Britain in their rivalry with the Dutch.

However, their rivalry cooled in 1824 when an Anglo-Dutch treaty demarcated their respective interests in Southeast Asia.

British rule in Burma began with the first Anglo-Burmese War (1824 – 1826).

Early World Mapping

Long before the era of global positioning satellites and multi-spectrum ortho-photography, ancient cartographers frequently

had to rely on word of mouth to describe far-away places. Sometimes, they would draw sea-monsters on maps to fill in the

empty spaces. Other times, they would expand the size of a place they had heard of, and add their own detail.

When the ancient mapmakers first began representing the earth’s surface on a map, they simply drew geographic features as

they saw them or as travelers and explorers described them. Because so little was known about the world, information on maps

was rather sparse and it was difficult to evaluate a map’s quality or accuracy. In fact, most maps created before the

European Renaissance were so generalized and inaccurate that the mapmakers could have assumed we lived on a flat earth and

it wouldn’t have made the slightest difference to the map’s usefulness.

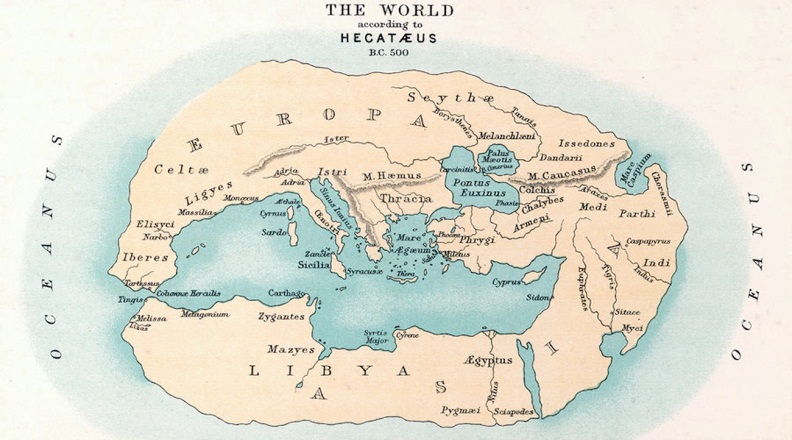

Hecataeus, a scholar of Miletus, probably produced the first book on geography in about 500 BC. A generation later

Herodotus, from more extensive studies and wider travels, expanded upon it. A historian with geographic leanings, Herodotus

recorded, among other things, an early circumnavigation of the African continent by Phoenicians. He also improved on the

delineation of the shape and extent of the then-known regions of the world, and he declared the Caspian to be an inland sea,

opposing the prevailing view that it was part of the “northern oceans”.

Figure 1. Reconstruction of the world map according to Hecataeus (ca 500

BC).

Although Hecataeus regarded the Earth as a flat disk surrounded by ocean, Herodotus and his followers questioned the concept

and proposed a number of other possible forms. Indeed, the philosophers and scholars of the time appear to have been

preoccupied for a number of years with discussions on the nature and extent of the world. Some modern scholars attribute the

first hypothesis of a spherical Earth to Pythagoras (6th century BC) or Parmenides (5th century). The idea gradually

developed into a consensus over many years. In any case by the mid-4th century the theory of a spherical Earth was well

accepted among Greek scholars, and about 350 BC Aristotle formulated six arguments to prove that the Earth was, in truth, a

sphere. From that time forward, the idea of a spherical Earth was generally accepted among geographers and other

scholars.

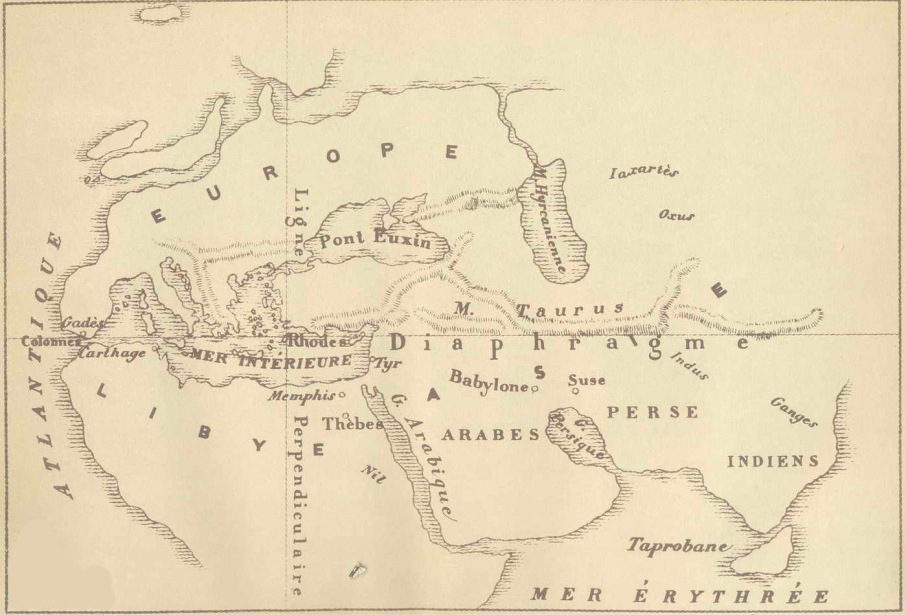

Figure 2. Reconstruction of the world map according to Herodotus (ca 430

BC).

About 300 BC, Dicaearchus, a disciple of Aristotle, placed an orientation line on the world map, running east and west

through Gibraltar and Rhodes. Eratosthenes, Marinus of Tyre, and Ptolemy successively developed the reference-line principle

until a reasonably comprehensive system of parallels and meridians, as well as methods of projecting them, had been

achieved.

Figure 3. Reconstruction of the world map according to Dicaearchus (ca 300

BC).

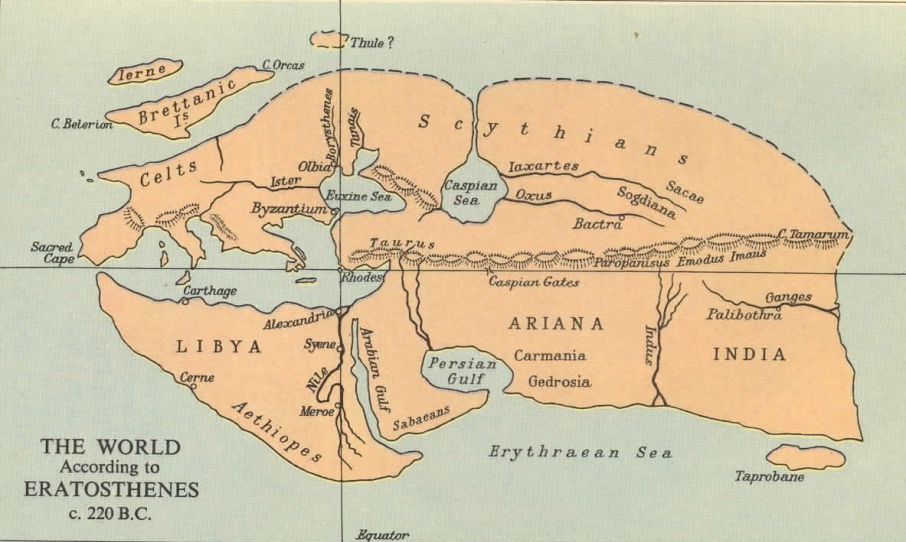

Eratosthenes (276 – 194 BC) drew an improved world map, incorporating information from the campaigns of Alexander the Great

and his successors. Asia became wider, reflecting the new understanding of the actual size of the continent. Eratosthenes

was also the first geographer to incorporate parallels and meridians within his cartographic depictions, attesting to his

understanding of the spherical nature of the earth.

Figure 4. 1883 reconstruction of Eratosthenes’ map

Posidonius (ca 150 – 130 BC) work “about the ocean and the adjacent areas” was

a general geographical discussion, showing how all the forces had an effect on each other and applied also to human life. He

measured the Earth’s circumference by reference to the position of the star Canopus. His measure of 240,000 stadia

translates to 24,000 miles, close to the actual circumference of 24,901 miles. He was informed in his approach by

Eratosthenes, who a century earlier used the elevation of the Sun at different latitudes. Both men’s figures for the Earth’s

circumference were uncannily accurate, aided in each case by mutually compensating errors in measurement. However, the

version of Posidonius’ calculation popularized by Strabo was revised by correcting the distance between Rhodes and

Alexandria to 3,750 stadia, resulting in a circumference of 180,000 stadia, or 18,000 miles. Ptolemy discussed and favored

this revised figure of Posidonius over Eratosthenes in his Geographia, and

during the Middle Ages scholars divided into two camps regarding the circumference of the Earth, one side identifying with

Eratosthenes’ calculation and the other with Posidonius’ 180,000 stadia measure. Depending on the value of the stadia that

is adopted, it may be true that Posidonius, seeking to improve on Eratosthenes, underestimated the size of the earth, and

this measurement, copied by Ptolemy, and was thereafter transmitted to Renaissance Europe.

Figure 5. A 1628 reconstruction of Posidonius ideas about the positions of

continents

Strabo (ca 64 BC – 24 AD) is mostly famous for his 17-volume workGeographica, which presented a descriptive history of people and places from different

regions of the world known to his era. The Geographica first appeared in

Western Europe in Rome as a Latin translation issued around 1469. Although Strabo referenced the antique Greek astronomers

Eratosthenes and Hipparchus and acknowledged their astronomical and mathematical efforts towards geography, he claimed that

a descriptive approach was more practical. Geographica provides a

valuable source of information on the ancient world, especially when this information is corroborated by other sources.

Within the books of Geographica is a map of Europe. Whole world maps

according to Strabo are reconstructions from his written text.

Figure 6. A 1815 reconstruction of the world map according to Strabo

Pomponius Mela (ca 43 AD) is unique among ancient geographers in that, after

dividing the earth into five zones, of which two only were habitable, he asserts the existence of antichthones, people inhabiting the southern temperate zone inaccessible to the folk of the

northern temperate regions due to the unbearable heat of the intervening torrid belt. On the divisions and boundaries of

Europe, Asia and Africa, he repeats Eratosthenes; like all classical geographers from Alexander the Great (except Ptolemy)

he regards the Caspian Sea as an inlet of the Northern Ocean, corresponding to the Persian (Persian Gulf) and Arabian (Red

Sea) gulfs on the south.

Figure 7. A 1898 reconstruction of Pomponius Mela view of the World.

The greatest figure of the ancient world in the advancement of geography and cartography was Claudius Ptolemaeus (Ptolemy;

90 – 168 AD). An astronomer and mathematician, he spent many years studying at the library in Alexandria, the greatest

repository of scientific knowledge at that time. He pioneered the use of curving parallels and converging meridians on maps.

Ptolemy’s maps were “Mediterranean specific”, very generalized, and almost completely ignored the Southern Hemisphere.

Still, they were a significant step forward in mapmaking and so far ahead of their time, they were used well into the

Renaissance.

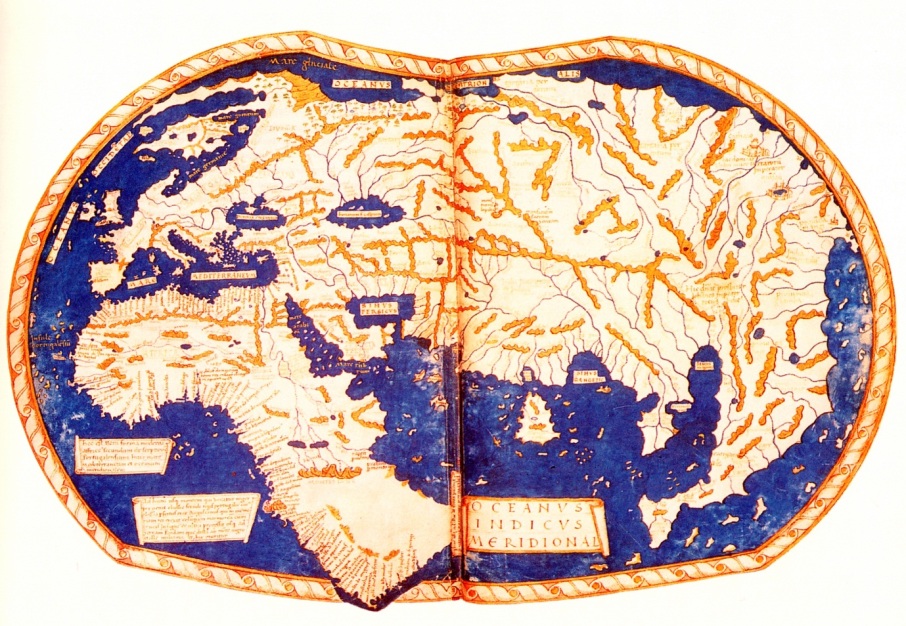

Figure 8. Ptolemy’s map of the world by Johane Schnitzer (Ulm: Leinhart Holle,

1482). The original map was lost.

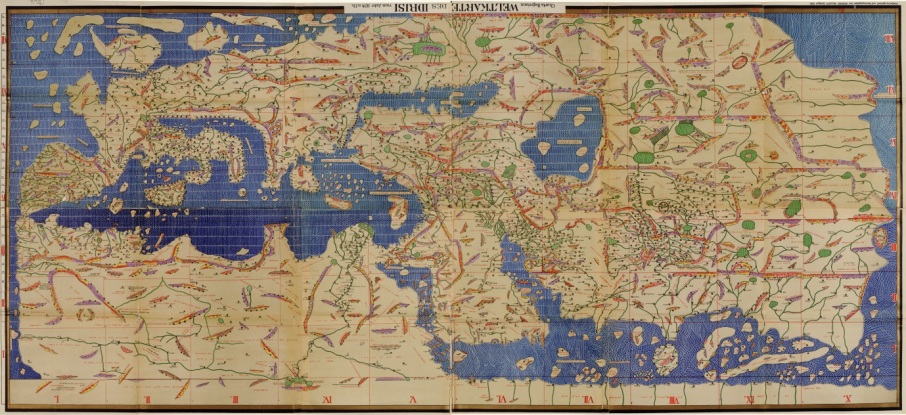

The Arab geographer, Muhammad Al-Idrisi (1154 AD), incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East

gathered by Arab merchants and explorers with the information inherited from the classical geographers to create the most

accurate map of the world at the time. It remained the most accurate world map for the next three centuries. TheTabula Rogeriana was drawn by Al-Idrisi in 1154 for the Norman King Roger II of

Sicily, after a stay of eighteen years at his court, where he worked on the commentaries and illustrations of the map. The

map, written in Arabic, shows the Eurasian continent in its entirety, but only shows the northern part of the African

continent.

Figure 9. The Tabula Rogeriana, drawn by Al-Idrisi for Roger II of Sicily in

1154

The world map of Henricus Martellus Germanus (Heinrich Hammer), ca 1490,

was remarkably similar to the terrestrial globe later produced by Martin Behaim in 1492, the Erdapfel. Both show heavy influences from Ptolemy, and both possibly derive from maps created around 1485

in Lisbon by Bartolomeo Columbus. Although Martellus is believed to have been born in Nuremberg, Behaim’s home town, he

lived and worked in Florence from 1480 to 1496.

Figure 10. Martellus world map (1490)

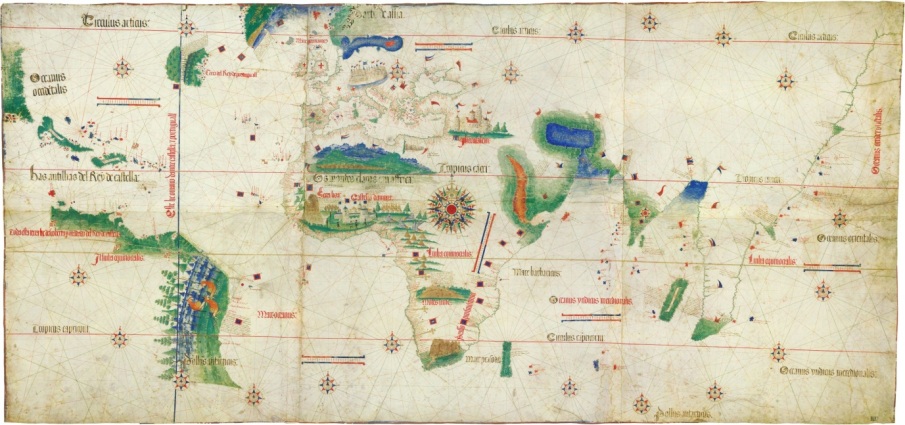

The Cantino planisphere or world map is the earliest surviving map

showing Portuguese geographic discoveries in the east and west. It is named after Alberto Cantino, an agent for the Duke of

Ferrara, who successfully smuggled it from Portugal to Italy in 1502. The map is particularly notable for portraying a

fragmentary record of the Brazilian coast, discovered in 1500 by the Portuguese explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral, and for

depicting the African coast of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans with a remarkable accuracy and detail. It was valuable at the

beginning of the sixteenth century because it showed detailed and up-to-date strategic information in a time when geographic

knowledge of the world was growing at a fast pace. It is important in our days because it contains unique historical

information about the maritime exploration and the evolution of nautical cartography in a particularly interesting period.

The Cantino planisphere is the earliest extant nautical chart where

places (in Africa and parts of Brazil and India) are depicted according to their astronomically observed latitudes.

Figure 11. Cantino planisphere (1502), Biblioteca Estense, Modena, Italy

The Caverio Map, also known as Caveri Map or Canerio Map, is a map drawn by Nicolay de Caveri, circa 1505. It is hand drawn

on parchment and colored, being composed of ten sections or panels, measuring 2.25 by 1.15 meters (7.4 by 3.8 feet).

Historians believe that this undated map signed with “Nicolay de Caveri Januensis” was completed in 1504 – 1505. It was

probably either made in Lisbon by the Genoese Canveri, or copied by him in Genoa from the very similar Cantino map. It shows

the east coast of North America with surprising detail, if the east coast of North America is compared with modern-day maps,

we will be struck by its immediately noticeable similarity with the coastline stretching from Florida to the Delaware or

Hudson River, when we consider the general belief that the Europeans neither saw nor set foot on the beaches in the southern

states of the present-day USA. It was one of the primary sources used to make the Waldseemüller map in 1507. Caverio map is

currently at Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris.

Figure 12. Caverio Map (ca 1505), Bibliothèque Nationale de France,

Paris

The story of the small group of Renaissance intellectuals that worked at San Die, a small city in the Alzace (France) from

1500 onwards is well known. The team was financed by Duc Rene II de Lorraine, represented in the team by Walter Ludd. Martin

Ringmann was the writer and Martin Waldseemüller the geographer. They set themselves to analyze new geographical information

coming from the earliest of voyages of discovery and integrate that information into existing maps and atlases. The effort

led to the publication of an important booklet, Universalis

Cosmographia (1507); one of the most important wall maps of the world ever published and a globe, published the

same year. From this revolution in cartography a new line of editions of Ptolemy’s Geographia was born (1513; 1520; 1522;

1535; 1541) which brought together old with new knowledge of the world.

Waldseemüller’s large world map was the most exciting product of that research effort, and included data gathered during

Amerigo Vespucci’s voyages of 1501 – 1502 to the New World. Waldseemüller christened the new lands “America” in recognition

of Vespucci’s understanding that a new continent had been uncovered as a result of the voyages of Columbus and other

explorers in the late fifteenth century. This is the only known surviving copy of the first printed edition of the map,

which, it is believed, consisted of 1,000 copies.

Waldseemüller’s map supported Vespucci’s revolutionary concept by portraying the New World as a separate continent, which

until then was unknown to the Europeans. It was the first map, printed or manuscript, to depict clearly a separate Western

Hemisphere, with the Pacific as a separate ocean. The map represented a huge leap forward in knowledge, recognizing the

newly found American landmass and forever changing the European understanding of a world divided into only three parts –

Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Figure 13. Universalis Cosmographia, the Waldseemüller wall map, 1507

Lorenz Fries (ca 1490 – ca 1531 AD) was a physician, astrologer and geographer who is perhaps best-known to cartophiles for his re-

working of Martin Waldseemüller’s maps from Claudius Ptolemy’s Geographia.

Karrow suggests in his Mapmakers of The Sixteenth Century and Their

Maps that Fries had studied at Vienna, Montpellier, Piacenza and Pavia before working in Schlettstadt, Colmar,

Fribourg and Strasbourg. Fries’ early publications were related to medicine and he experienced some success in this field.

His publisher was Gruninger, in Strasbourg, who was also known to have worked in collaboration with Waldseemuller on

the Chronica Mundi, a cosmography planned for publication. It seems likely

that this small volume was to help form Fries’ considerable involvement with Waldseemüller maps. The first of

Waldseemüller’s map to receive a re-working by Fries, and also worked on by Peter Apian, was the Tipus Orbis Universalis in 1520, which was based on Waldseemüller’s 1507 map of the world.

Figure 14. Tipus Orbis Universalis, a re-working of Waldseemüller’s map by Lorenz

Fries and Peter Apian, 1520

At the same time as this world map was being published, Fries was also working on an edition of Ptolemy’s “Geographia”. The

aforementionedChronica Mundi did not reach publication, perhaps because of

Waldseemüller’s death in 1518, and Gruninger, the publisher, decided instead to have Fries work on an edition of Ptolemy

using the maps that might have otherwise been included in the Chronica Mundi.

Thus, Fries’ first edition of Waldseemüller’s Ptolemy appeared in Strasbourg in 1522 – it was very similar to

Waldseemüller’s own 1513 version although Fries’ maps were cut at a slightly reduced size. Three maps were new to this

edition (although were based on Waldseemüller’s map of 1507); the world, South-East Asia and eastern Asia (showing China and

Tartary). Fries’ woodblocks were used again in three subsequent editions of 1525, published in Strasbourg and edited by

Willibald Pirkheimer in 1535, published in Lyons and edited by Michael Servetus in 1541, also published in Lyons – a re-

print of the 1535 edition.

Figure 15. World map from Ptolemy, Geographia, edited by Lorenz Fries,

1522

Abraham Ortelius (1527 – 1598 AD) was conventionally recognized as the creator of the first modern atlas. In 1564 he

published his first map, Typus Orbis Terrarum, an eight-leaved wall map of the

world, on which he identified the Regio Patalis with Locach as a northward extension of the Terra Australis, reaching as far

as New Guinea. Many of his atlas’ maps were based upon sources that no longer exist or are extremely rare. Ortelius appended

a unique source list (the Catalogus Auctorum) identifying the names of

contemporary cartographers, some of whom would otherwise have remained obscure.

Figure 16. Typus Orbis Terrarum by Abraham Ortelius (1564 AD)

Ptolemy’s World Map

Claudius Ptolemaeus, better known as Ptolemy (ca 90 – 168 AD) made many

important contributions to geography and spatial thought. A Greek by descent, he was a native of Alexandria in Egypt, and

became known as the most wise and learned man of his time. Although little is known about Ptolemy’s life, he wrote on many

topics, including geography, astrology, musical theory, optics, physics, and astronomy.

Ptolemy’s text reached Italy from Constantinople in about 1400 and was translated into Latin by Jacobus Angelus of Scarperia

around 1406. The first printed edition with maps, published in 1477 in Bologna, was also the first printed book with

engraved illustrations. Many editions followed (more often using woodcut in the early days), some following traditional

versions of the maps, and others updating them. An edition printed at Ulm in 1482 was the first one printed north of the

Alps. Also in 1482, Francesco Berlinghieri printed the first edition in vernacular Italian.

Ptolemy’s work in astronomy and geography have made him famous for the ages, despite the fact that many of his theories were

in the following centuries proven wrong or changed. Ptolemy collected, analyzed, and presented geographical knowledge so

that it could be preserved and perfected by future generations. These ideas include expressing locations by longitude and

latitude, representing a spherical earth on a flat surface, and developing the first equal area map projection. Ptolemy’s

accomplishments reflect his understanding of spatial relationships among places on earth and of the Earth’s spatial

relationships to other celestial bodies.

The greatest contribution of Ptolemy was not the maps themselves but the concepts behind the maps. Geographia, a work of seven volumes, the standard geography textbook until the 15th century,

transmitted a vast amount of topographical detail to Renaissance scholars, profoundly influencing their conception of the

world. Containing instructions for drawing maps of the entire oikoumenè

(inhabited world), Geographia was what we would now call an atlas. It

included a world map, 26 regional maps, and 67 maps of smaller areas.

He illustrated three different methods for projecting the Earth’s surface on a map (an equal area projection, a

stereographic projection, and a conic projection), and the calculation of coordinate locations for some eight thousand

places on the Earth. He invented the concept of latitude and longitude, a mapping system still commonly used today. Latitude

was measured horizontally from the equator, but Ptolemy preferred to express it as the length of the longest day rather than

degrees of arc (the length of the mid-summer day increases from 12h to 24h as one goes from the equator to the polar

circle), while longitude was measured from the westernmost landmass known to date, El Hierro, one of the Canary Islands off

the coast of Spain. Through his publications, Ptolemy dominated European cartography for nearly a millennium and inspired

explorers like Christopher Columbus to test the spatial boundaries of the world. Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about

only a quarter of the globe.

Ptolemy had mapped the whole world from the Fortunatae Insulae (Cape Verde or Canary Islands) eastward to the eastern shore

of the Magnus Sinus. This known portion of the world was comprised within 180 degrees. In his extreme east Ptolemy placed

Serica (the Land of Silk), the Sinarum Situs (the Port of the Sinae), and the emporium of Cattigara. On the 1489 map of the

world by Henricus Martellus, which was based on Ptolemy’s work, Asia terminated in its southeastern point in a cape, the

Cape of Cattigara. Cattigara was understood by Ptolemy to be a port on the Sinus Magnus, or Great Gulf, the actual Gulf of

Thailand, at eight and a half degrees north of the Equator, on the coast of Cambodia, which is where he located it in his

Canon of Famous Cities. It was the easternmost port reached by shipping trading from the Graeco-Roman world to the lands of

the Far East.

His ability to take in and understand the incredible amount of information developed before his time, add to it, and

synthesis it into a map or a book of maps changed how people understood, perceived, and represented the world. Copies and

reprints of Ptolemy’s world maps made up the majority of navigation and factual maps for centuries to come, providing the

base information for early European explorers. Ptolemy also standardized the orientation of maps, with North at the top and

East on the right, thereby placing the known world in the upper left, a standard that remains to this day.

Geographia carried a list of the names of some 8,000 places and their

approximate latitudes and longitudes. Except for a few that were made by observations, the greater numbers of these

locations were determined from older maps, with approximations of distances and directions taken from travelers. In spite of

the more accurate mapping of both Philo and Josephus 100 years earlier, Ptolemy carries on the long tradition of Greek

geographers (Strabo, Eratosthenes, Herodotus, Hesiod and Hecataeus).

We know very little of Ptolemy’s life. He made astronomical observations from Alexandria in Egypt during the years 127 – 141

AD. The first observation which we can date exactly was made by Ptolemy on 26 March 127 while the last was made on 2

February 141. In fact there is no evidence that Ptolemy was ever anywhere other than Alexandria.

It is not surprising that the maps given by Ptolemy were quite inaccurate in many places for he could not be expected to do

more than use the available data and this was of very poor quality for anything outside the Roman Empire, and even parts of

the Roman Empire are severely distorted. One fundamental error that had far-reaching effects was attributed to Ptolemy – an

underestimation of the size of the Earth. He showed Europe and Asia as extending over half of the globe, instead of the 130

degrees of their true extent. Similarly, the span of the Mediterranean ultimately was proved to be 20 degrees less than

Ptolemy’s estimate. So lasting was Ptolemy’s influence that 13 centuries later Christopher Columbus underestimated the

distances to Cathay and India partly from a recapitulation of this basic error.

The prevailing method of mapping in the ancient world was by means of topological itinerary maps and gazetteers that

provided their users with useful travel guides. Of primary concern to most travelers was knowledge of definite and

relatively unhazardous routes. The idea of a world map that placed locations relative to an independent spatial framework,

whilst certainly a fascinating scientific curiosity, was both too inaccurate and too uninformative (of terrain, winds, sea

currents, etc) to be of any practical use. Ptolemy was fully aware that

copying a visual map was guaranteed to introduce a great quantity of error. It also makes vividly clear why attempts to

correlate Ptolemy’s map with known locations are rendered more or less unviable. In order to reduce these problems of

transmission, his Geographia is separated into two parts. The first,

along with his methodology, describes how to draw a map according to two different projections. The second is a catalogue of

locations, listing both towns and notable geographical features with their latitude and longitude.

The continents are given as Europe, Asia, and Libya (Africa). The World Ocean is only seen to the west. The map

distinguishes two large enclosed seas: the Mediterranean and the Indian (Indicum Pelagus). Due to Marinus and Ptolemy’s

mistaken measure of the circumference of the earth, the former is made to extend much too far in terms of degrees of arc;

due to their reliance on Hipparchus, they mistakenly enclose the latter with an eastern and southern shore of unknown lands,

which prevents the map from identifying the western coast of the World Ocean. India is bound by the Indus and Ganges Rivers,

but its peninsula is much shortened. The Malay Peninsula is given as the Golden Chersonese instead of the earlier “Golden

Island”, which derived from Indian accounts of the mines on Sumatera (or Kalimantan). Beyond the Golden Chersonese, the

Great Gulf (Magnus Sinus) forms a combination of the Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea which is bound by the unknown

lands thought to enclose the Indian Sea. China is divided into two realms – the Qin (Sinae) and the Land of Silk (Serica) –

owing to the different accounts received from the overland and maritime Silk Roads.

Definitions of India

In medieval Europe the concept of “three Indias” was in common circulation. Greater India was the southern part of South

Asia, Lesser India was the northern part of South Asia, and Middle India was the region around Ethiopia. The name Greater

India (Portuguese: India Maior) was used at least from the mid-15th century.

The term, which seems to have been used with variable precision, is sometimes meant only the Indian subcontinent; Europeans

used a variety of terms related to South Asia to designate the South Asian peninsula, including High India, Greater India,

Exterior India and India Aquosa.

However, in some accounts of European nautical voyages, Greater India (orIndia

Major) extended from the Malabar Coast (present-day Kerala) to India extra

Gangem (“India, beyond the Ganges”, but usually the East Indies, iepresent-day Southeast Asian archipelago) and India Minor, from

Malabar to Sind. Farther India was sometimes used to cover all of modern Southeast Asia and sometimes only the mainland

portion.

In late 19th-century geography, “Greater India” referred to Hindustan (Northwestern Subcontinent) which included the Punjab,

the Himalayas, and extended eastwards to Indochina (including Burma), parts of Indonesia (namely, the Sunda Islands,

Kalimantan and Sulawesi), and the Philippines. German atlases sometimes distinguished Vorder-Indien (Anterior India) as the South Asian peninsula and Hinter-Indien as Southeast Asia.

The Island of Taprobana

Taprobana, under the name of the “land of the Antichthones” or Opposite-Earth, was long looked upon as another world. The

name was entirely unknown in Europe before the time Alexander the Great invaded India in in 327 BC. The writers who speak of

Taprobana are Onesicritus, Eratosthenes, Megasthenes, Hipparchus, Strabo, and Pliny.

There are two distinct periods in which Taprobana is mentioned; and a third period when the site, with the name itself, have

utterly vanished. The first period is that of the early and ancient writers from the time of Alexander the Great to that of

the Emperor Claudius. It embraces notices from Onesicritus, Megasthenes, and Pliny. They all use no other name than that of

Taprobana. The second period embraces the time from Ptolemy to that of Cosmas Indicopleustes, late on into the Christian

era.

About twenty years after Alexander’s death, Megasthenes was sent as ambassador by Seleucus Nicator in 302 BC to Sandracottus

(Chandragupta Maurya). From information derived at the court of Sandracottus, Megasthenes described Taprobana as a very

fertile island divided by a river. One part was infested by wild beasts and elephants, and the other inhabited by Prachii

colonists, and producing gold and gems.

Eratosthenes has also given the dimensions of this island, as being 7,000 stadia in length, and 5,000 in breadth. He states

also that there were no cities, but villages to the number of 700. It began at the Eastern sea, and laid extended opposite

to [Greater] India, east and west. This island was in former times supposed to be 20 days’ sail from the country of the

Prasii, but in later times, whereas the navigation was formerly confined to vessels constructed of papyrus with the tackle

peculiar to the Nile, the distance had been estimated at no more than 7 days sail, in reference to the speed which could be

attained by vessels of their construction.

According to Pliny, in the reign of Claudius (41 – 54 AD), a freedman Annius Plocamus, who had farmed from the treasury the

Red Sea revenues, while sailing around Arabia was carried away by gales of wind from the north beyond Carmania. In the

course of 15 days he had been wafted to Hippuri, a port of Taprobana, where he was humanely received, hospitably entertained

by the king, and having in six months time to acquire the language. This king, moreover, was so impressed with the character

of the Romans, as exhibited by the fact that the denarii found in the possession of the freedman were all of equal weight,

although the different figures on them plainly showed that they had been struck in the reigns of several emperors. He

remained there sometime longer, and brought them acquainted with his own government. He dispatched the embassy in question

to Rome, consisting of 4 ambassadors, of whom the chief was Rachia.

Strabo gathered many details from the ambassadors. Taprobana contained 500 towns and villages, and that there was a harbor

that lies facing the south, and adjoining the city of Palaesimundus, 10 the most famous city in the isle, the king’s place

of residence, and containing a population of 200,000. There was a lake in the country called Megisba, 375 miles in

circumference, from which one river called Palaesimundus, ran by the capital of that name, by 3 channels, the narrowest of

which was 5 stadia in width, the largest 15; and the other, Cydara by name, northwards towards the coast of India. There

were corals, pearls, and precious stones; the soil was fruitful; life was prolonged to more than a hundred years; there was

a trade with China overland. The king wears the costume of Father Liber. Their festivals are celebrated with the chase, the

most valued sports being the pursuit of the tiger and the elephant. The lands are carefully tilled; the vine is not

cultivated there, but of other fruits there is great abundance. They take great delight in fishing, and especially in

catching turtles; beneath the shells of which whole families find an abode, of such vast size are they to be found. The mode

of trade and barter among the inhabitants themselves was peculiar, being done at night. The country and people were maritime

and highly commercial. These ambassadors made one statement of the country enjoying two summers and two winters, which

clearly show that the country embraced on both sides of the equator.

The inhabitants, who lived a hundred years, spent most of their time in hunting tigers and elephants, and fishing,

especially catching turtles, whose shells were so enormous habitations were made of them. The ambassadors expressed great

surprise at seeing the northern stars, and the sun rise on the left and set on the right hand. The nearest point of the

[Greater] Indian coast was a promontory known as Coliacum, distant 4 days’ sail, and midway between them lay “the island of

the Sun”; the sea was a greenish tint, having numerous trees (coral) growing in it, which the rudders of vessels broke off

as they came in contact when sailing over it.

The sea that lies between the island and the mainland is full of shallows, not more than 6 paces in depth; but in certain

channels it is of such extraordinary depth, that no anchor has ever found a bottom. For this reason it is that the vessels

are constructed with prows at either end; so that there may be no necessity for tacking while navigating these channels,

which are extremely narrow. The tonnage of these vessels is 3,000 amphorae. In traversing their seas, the people of

Taprobana take no observations of the stars, and indeed the Greater Bear is not visible to them; but they carry birds out to

sea, which they let go from time to time, and so follow their course as they make for the land. They devote only 4 months in

the year to the pursuits of navigation, and are particularly careful not to trust themselves on the sea during the next 100

days after the summer solstice, for in those seas it is at that time the middle of winter.

Ptolemy, referring to Taprobana, states that its name had been altered to Salike. While Pliny gives very few names of places

in Taprobana, Ptolemy, on the contrary, supplies a mass of information concerning the island, which is surprising by its

copiousness, including not merely a complete periplus of its coasts, with the names of the headlands, rivers, and seaport

towns, but also the names of many cities and tribes in the interior.

Figure 17. Ptolemy’s Taprobana as published in Cosmographia Claudii Ptolomaei

Alexandrini, 1535

The Periplus Maris Erythraei (or “Voyage around the Erythraean Sea”), an

anonymous work from around the middle of the first century AD written by a Greek speaking Egyptian merchant, indicates that

the course trending toward the east, lying out at sea toward the west is the island Palaesimundu, called by the ancients

Taprobana. The northern part is a day’s journey distant, the southern part trends gradually toward the west, and almost

touches the shore of Azania. It produces pearls, transparent stones, muslins and tortoise-shell.

Cosmas Indicopleustes (Cosmas the Indian Voyager), who wrote The Christian

Topography in the early 6th century, took especial care several times to impress it on his readers that the island

called Serendib by the Indians was the Taprobana of the earlier Greeks. In the time of Cosmas the name Taprobana had

vanished.

Kalimantan Hypothesis for Taprobana

From the BC until the Middle Ages followed by the New World, a wide variety of world maps had been created and can be

observed, which shows the development of the Western knowledge about the whole Earth, from the simple to the almost

complete. The development was driven by the need for more accurate maps of trade routes heading to the world in the east,

known as “The Silk Road”, that is from the Mediterranean Sea, followed by the Red Sea, the Erythraean Sea, the Indian Ocean,

and ending in China. At the early century, only that trade route was the most widely known, while outside those regions only

little information obtained that were from sailors who had visited them. Kalimantan Island is outside that route so that the

location was not exactly known, or possibly deliberately kept in secret because this island has lucrative resources with

superior quality that are very alluring for trade commodities. These become the subjects of the author to hypothesize that

Taprobana is actually Kalimantan.

World Map Development

The island of Taprobana is shown on Dicaearchus (300 BC), Eratothenes (220 BC), Strabo (18 AD), Pomponius Mela (43 AD),

Ptolemy (150 AD), Al-Idrisi (1154), Martellus (1490 AD), Cantino (1502 AD), Caverio (1505 AD), Waldseemüller (1507 AD),

Lorenz Fries/Peter Apian (1520 AD) and edited Ptolemy’s by Lorenz Fries (1522 AD), while the Middle-Age maps by Abraham

Ortelius (1570 AD) and after do not show.

Maps prior to Ptolemy were without advancement of geography and cartography, so that information on maps was rather sparse,

so generalized and inaccurate. Geographic features were drawn as they saw them or as travelers and explorers described them.

As begun by Dicaearchus in the 3rd or 4th century BC, Taprobana was put, on the world map, as what they heard from what they

saw or described by other travelers, in the Indian Ocean without knowing the exact position, at the south, west or further

west of the Indian promontory.

Ptolemy’s map shows the whole world from the Fortunatae Insulae eastward to China, spanned 180 degrees of longitude

and about 80 degrees of latitude. His book Geographia carried a list of

the names of some 8,000 places and their approximate latitudes and longitudes. The greater number of these locations were

determined from older maps (Strabo, Eratosthenes, Herodotus, Hesiod and Hecataeus), with approximations of distances and

directions taken from travelers and more accurate mapping of both Philo and Josephus 100 years earlier, except for a few

that were made by observations. Ptolemy was well aware that he knew about only a quarter of the globe and could not do more

as the available data was of very poor quality for anything outside the Roman Empire. These make the maps given by Ptolemy

are inaccurate in many places. If we look his world map and compare it with the modern map, we can clearly see the

tremendous deviations, much largely in the Asian portion. His error of underestimation of the size of the Earth is another

contribution of the inaccuracy.

Ptolemy also included 26 regional maps and 67 maps of smaller areas. These maps are at the grater located in and around the

Roman Empire, with only a few regional maps are in the Greater India and China, among them is Taprobana. These regional maps

and smaller area data were of better accuracy, whether obtained from his observations or data from other travelers or

explorers. Putting these regions and areas on an inaccurate world map derived from the older maps creates confusions to

locate their exact positions. Allegedly, he located Taprobana based on the older maps of whether Eratothenes or Strabo, that

actually no such island was in the position, or he deliberately put it in the wrong place or floated its location so that

not everyone can get there. However, so far ahead of their time, they were used well into the Renaissance until 13 centuries

later Christopher Columbus underestimated the distances to Cathay and India.

With the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, the land route to Asia became much more difficult and

dangerous. This resulted in a lack of information of the area encompassed by the Indian Ocean, until the Portuguese

explorers developed a passage to Asia by sailing around Africa and with the conquest of the Sultanate of Malaka in 1511.

Thus, the Asian portion of the world maps after Ptolemy still continued to rely on his information found in the Geographia, incorporated the knowledge obtained from the Arab explores and unknown

sources, as shown on the maps of Al-Idrisi, Martellus, Cantino, Caverio, Waldseemüller, Fries and Apian. Al-Idrisi

incorporated the knowledge of Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Far East gathered by Arab merchants and explorers. Martellus’

map shows heavy influences from Ptolemy but incorporated Africa. Cantino’s map portrays Brazilian coast and depicts African

coast of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans with a remarkable accuracy and detail. Caverio’s map shows the east coast of North

America with surprising detail where its sources are still a mystery. Waldseemüller’s map is a new line of editions of

Ptolemy’s Geographia with the integration of new geographical information

coming from the earliest of voyages of discovery. Fries and Apian’s maps are re-working of the Waldseemüller’s map. Most of

these maps located Taprobana more or less on the same position as Ptolemy’s map, except Cantino and Caverio’s maps portrayed

it as Sumatera.

Observing and comparing Ptolemy’s and Martellus’ maps, we can clearly see that there were confusions in mapping the Indian

Peninsula. Ptolemy describes it in two major regions, India Intra Gangem in the west that does not show a major protruding

peninsula (where there are Laricae Ariasa and Lymirca), and India Extra Gangem in the east that shows a major protruding

peninsula (where there is Aurrea Chersonenus). He mapped Indus and Ganges at the west and east of India Intra Gangem,

respectively, and Sinus Magnus at the east of India Extra Gangem. Martellus added another peninsula in the east (where there

is Catigara) based on Ptolemy’s data, and kept the others similar to Ptolemy’s. This peninsula is supposedly to be the Malay

Peninsula so that the Indian Peninsula should be the Ptolemy’s India Extra Gangem. Maps thereafter by Cantino, Caverio,

Waldseemüller, Fries and Apian confirm this.

Figure 18. Clarified Ptolemy’s map

Figure 19. Clarified Martellus’ map

The Cantino and Caverio’s map shows two islands depicting Ceylam (Sri Lanka) and Taprobana (Sumatera). The Waldseemüller,

Fries and Apian’s maps are the maps showing Seyla or Seylam (Sri Lanka) and Iava Minor (probably Sumatera) along with

Taprobana but further west. These become an indication that Taprobrana is not Sri Lanka or Sumatera, and an allegation that

it deliberately put in the wrong place or floated its location for secrecy. It is allegedly that sailors trying to find

Taprobana using Ptolemy’s and Ptolemy based maps could not find it in the location but then sailed further, at the end found

Sumatera and assumed it as Taprobana.

Abraham Ortelius’ map is the first modern atlas that includes almost the major islands and places in the Greater India. In

addition to showing Zeilan (Sri Lanka) and Sumatra, Taprobana disappears and Burneo (Kalimantan) and other islands in the

archipelago were added. Thus, it shows the incredibly improved knowledge of the cartographers in that time.

Geographic Conditions of Taprobana

Eratosthenes mentioned that Taprobana is located in Eastern sea, lies extended opposite to Greater India. He gave the

dimensions of the island, as being 7,000 stadia (≈ 1,300 km) in length, and 5,000 (≈ 925 km) in width. When we measure the

size of Kalimantan Island, we can find that these dimensions are highly accurate. The ambassadors dispatched to Rome, as

written by Pliny and Strabo, made one statement of the country enjoying two summers and two winters, which clearly show that

the country embraced on both sides of the equator. These become evidence that Eratosthenes, Pliny and Strabo are correct to

refer Taprobana as Kalimantan.

Pliny and Strabo stated that the nearest point of the Greater Indian coast was a promontory known as Coliacum, distant 4

days’ sail, and midway between them laid “the island of the Sun”. The sea was a greenish tint, having numerous coral at the

bottom, which the rudders of vessels broke off as they came in contact when sailing over it. The Coliacum promontory is

allegedly the Malay Peninsula, probably they gave its name referring to Kelantan or its older name Kalantan located in east

coast of the peninsula. The early history of Kelantan traces distinct human settlement dating back to prehistoric times, and

became an important center of trade by the end of the 15th century.

Between Kalimantan and the Malay Peninsula lays the Karimata Strait, a shallow water which was a land mass during the Ice

Age. Almost a hundred of islands and coral reefs are in this strait – administratively under the Riau Islands and Bangka-

Belitung Provinces of Indonesia – with main islands among them are Natuna, Anambas, Bintan, Lingga, Bangka and Belitung.

People in these islands are famous for their sun worshiping. The sea is shallow and reefs are on the bottom so that its

color is greenish.

There are several islands around the Kalimantan Island. Those in the Java Sea and Karimata Strait, where they have shallow

depth of about 20 to 50 meters, are a mix of real islands and coral reefs. In between islands or reefs, the depths are even

shallower so that vessels have to be carefully prepared for such condition. These confirm Pliny’s and Strabo’s

statements.

Figure 20. Kalimantan Island and its surroundings

The Dayak people inhabiting the Kalimantan Island are mostly hunters and farmers. Their leaders wear clothes and accessories

just like Father Liber, as what Pliny and Strabo said. They have also the most ancient tradition of tattooing. Animals are

abundant and the soil is fertile. The island is also rich of metal minerals such gold, silver and copper, and any kinds of

precious stones. Oysters producing pearls are cultivated in the seas around the island, now become 40% of the world supply

of pearl.

Elephants, tigers and turtles were abundant in the island as depicted by the Dayak traditions, languages and legends of how

they aware of the habitat and habits of these animals, but because of their tradition of hunting these animals, their

present populations are dwindled or extinct. Indonesia was the place of the ancient Stegodon, a large size elephant-like

animal. DNA Analysis indicates that Asian elephants are native to Kalimantan (Fernando et al, 2003). The now endangered Kalimantan pigmy elephants (Elephas maximus

borneensis) are what remained in Kalimantan now, the same species in Java is already extinct some 200 years ago.

Kalimantan, as well as Sumatera, are the habitat of giant turtles (Orlitia

borneensis) and clouded leopards (Neofelis nebulosa). These facts confirm

Pliny’s, Strabo’s and Ptolemy’s statements.

In daily life, helmeted hornbills (Rhinoplax vigil) are admired by the Dayak in

Kalimantan, for the lessons the community can learn from the behavior of the species. Using many different reverential names

for the birds, the Dayak have many myths and legends in which hornbills are envoys of the gods with the task of conveying

divine messages. In their beliefs, the birds give living examples of fidelity to a spouse and responsibility for family

life. The Dayak teach their children not to hurt or kill the sacred birds. Such deeds are a taboo. Pliny and Strabo said

that in traversing their seas, the people of Taprobana take no observations of the stars, but they carry birds out to sea,

which they let go from time to time, and so follow their course as they make for the land. These birds were apparently the

hornbill admired by the Dayak.

Pliny and Strabo stated that the island had a harbor at the south coast, adjoining the city of Palaesimundus. There was a

large lake named Megisba from which Palaesimundus River ran by the city by 3 channels each having width of between 5 and 15

stadia (about 925 and 2775 meters), and the Cydara River laid north of the lake. These three rivers were allegedly the

Barito, Kapuas-Murung and Kahayan Rivers. Barito River is nearly 3 kilometers, Kapuas-Murung River is about 1 kilometer and

Kahayan river is about 1.5 kilometers in width, in those parts near the sea, that show cnformities with those stated by

Pliny and Strabo. A large lake was probably formed on the plain region due to occurrence of a large flood from the mountains

with higher flow velocity that could erode the upper part of the plain, but the lower part is flat and level so that the

velocity was much reduced and the eroded material settled on that place forming a dam and a lake. A shallow lake on a flat

plane may vanish only within hundreds of years. The existing condition now is a large swampy region.

According to the old maps, Tanjungpura located on the south coast of Kalimantan was a prominent city. Several ancient

manuscripts mention also this name. Its literal meaning is “the city (pura) of Tanjung tree”. Tanjung tree (Mimusops elengi) is a medium-sized evergreen tree found in tropical forests in South Asia,

Southeast Asia and northern Australia. English common names include Spanish cherry, medlar, and bullet wood. Its Sanskrit

name is “bakula” so that an ancient manuscript from the Javanese Singasari Kingdom refers the city as Bakulapura. “Tanjung”

can also mean “cape” or “peninsula” as used in some place names, but not for this case.

In the history records, there was a community near the present Tanjung town named Tanjungpuri. One of the remains is a Hindu

temple Candi Agung located in Sungaimalang Village, Central Amuntai Sub-district, Hulu Sungai Utara Regency, South

Kalimantan Province. Carbon dating to the remains resulted in around 200 BC. Tanjungpuri was probably the primordial

Tanjungpura. The port of Hippuri mentioned by Pliny was probably Tanjungpuri.

At first, the indigenous people of Kalimantan did not apply the kingship system. Their social lives were based on customs

and beliefs that were developed and transmitted from generation to generation. The community was formed from a small number

of people and an amount of land necessary for living and farming. As the time over, they developed into a larger community

that made their customs a more complex, and need more land too. Opening a new land would create a new community so that over

time several communities were created but followed the same customs and inhabiting the same region. They called the whole

community having the same socio-cultural practices and inhabiting in a region “banua”, meaning “world”, similar to “mundus”

in Latin. The communities in Kalimantan strongly hold this “banua” concept until today.

Their social leader is called “raja” or “rajah”. The name of the chief of the embassy to Roman as stated by Pliny, Rachia,

is probably this “rajah”. James Brooke was appointed as “rajah”, ruling the territory across the western regions of Sarawak

in the 19th century.

Kingship was introduced into the indigenous by the Malay settlers from Sumatera around the 4th or 5th century. Tanjungpura

was probably a “banua” in the early centuries and BC, so that the long name would be “Banua Tanjungpura”. Some old maps

mention it as “Taiopuro”, which probably the European then called it with a long name “Taiopuro Banua”. To match the two consonants for each word, it was shortened to “Tapro Bana” and also to name the whole island, the same meaning as “Banua

Tanjungpura”.

About the name of “Salike” given by Ptolemy, there is an Austronesian word “salaka” that means “white-colored metal”. This

is probably a mixture of gold and silver, an electrum. This metal can be found naturally in southern Kalimantan region as a

byproduct of gold mining. The word is applied to a cape name, Tanjung Salaka, located at the south coast of Kalimantan

almost around the location of Tanjungpura.

The freedman Annius Plocamus was possibly stranded around the present-day Banjarmasin, in accordance with his statement that

on the southern coast of Taprobana. It was also said that its territory was divided into two separated by a river. One part

was infested by wild beasts and elephants, and the other inhabited by Prachii colonists, and producing gold and gems. The

river was possibly the present-day Barito River and the Prachii colonists was the present-day Banjar people which were

inherently colonists in several islands in Indonesia. On the ancient maps, the Banjar people were mentioned as Paco, Bancy,

Biajo, Bander and Banjar, and by Ptolemy as Bacchi. Banjarmasin by Odoric of Pordenone (an Italian Franciscan friar) was

mentioned as Thalamasyn. Banjarmasin by the Roman tongue was changed into Palaesi and added mundus (town) became Palaesimundus.

Alexander the Great and the Roman Empire possibly deliberately kept the actual name in secret and obscured it with another

names because this island has lucrative resources with superior quality that are very alluring for trade commodities.

Besides some other classic names of the island, Kalimantan bore the name of Nusakencana, literally means “the island of

gold”, as stated in the Jayabaya Prophecy from the Javanese Kediri Kingdom in the 12th century. The Muarakaman inscriptions

found in the upper region of Mahakam River in east Kalimantan dated to 4th century also attest that the king of Mulawarman

held a charity of much gold. The word “nusakencana” is an Austronesian language; its translation into Sanskrit is

“suwarnadwipa”. Suwarnadwipa is widely known as the island of Sumatera by the historians but there is no such inscription

that clearly refers it as the said island, so that other alternative of Suwarnadwipa is Kalimantan as this island is more

abundant with gold than Sumatera. Moreover, Cosmas Indico-pleustes mentioned that “Serendip”, a European tongue of

“Suwarnadwipa”, was the island of Taprobana.

Ancient Maps of Kalimantan

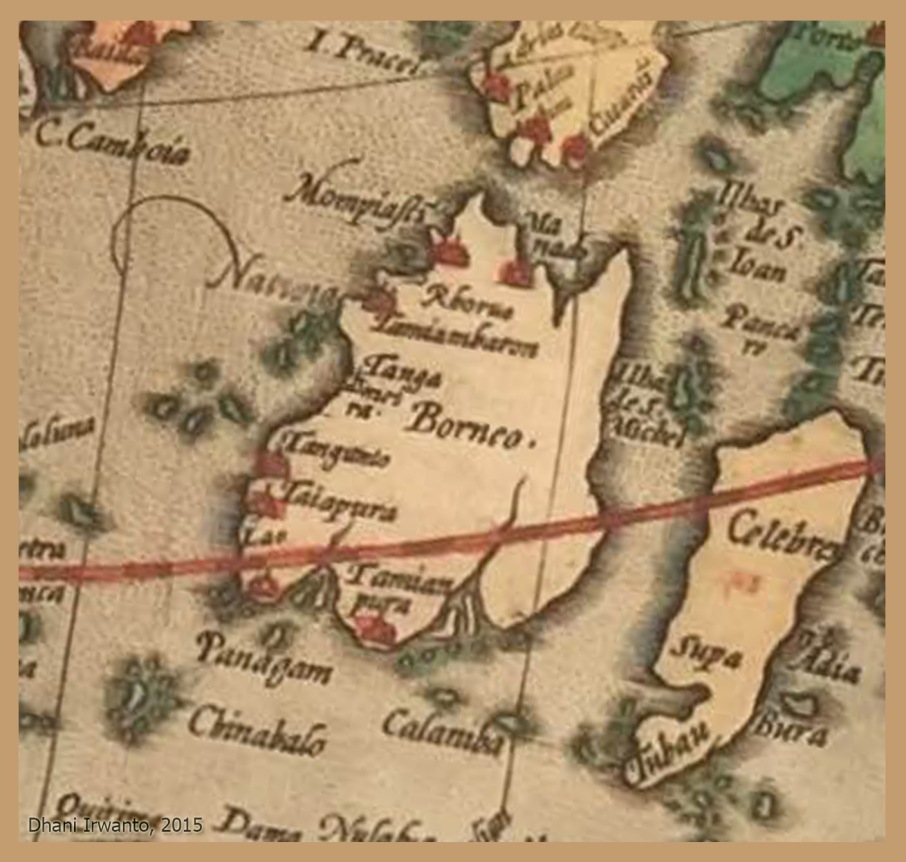

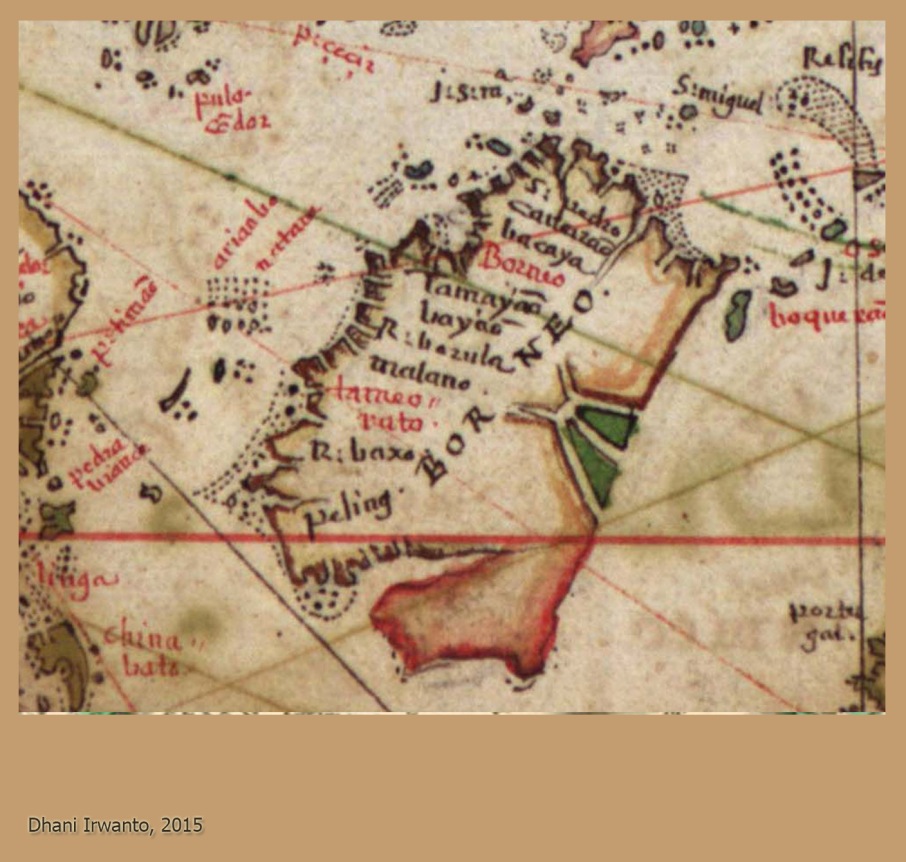

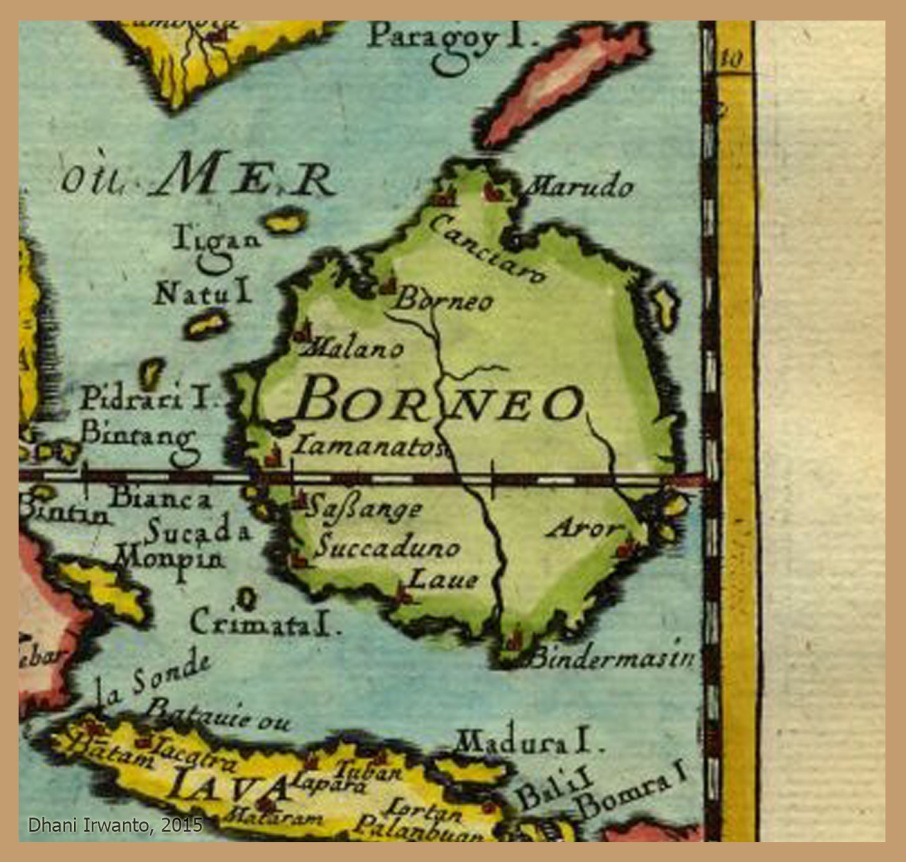

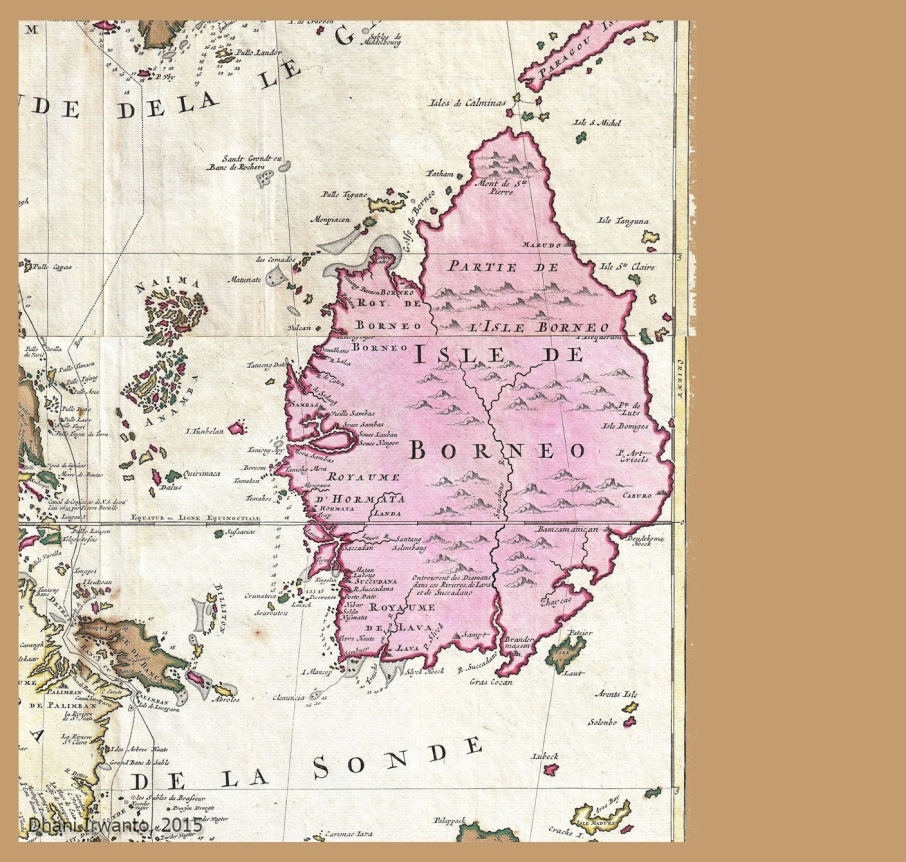

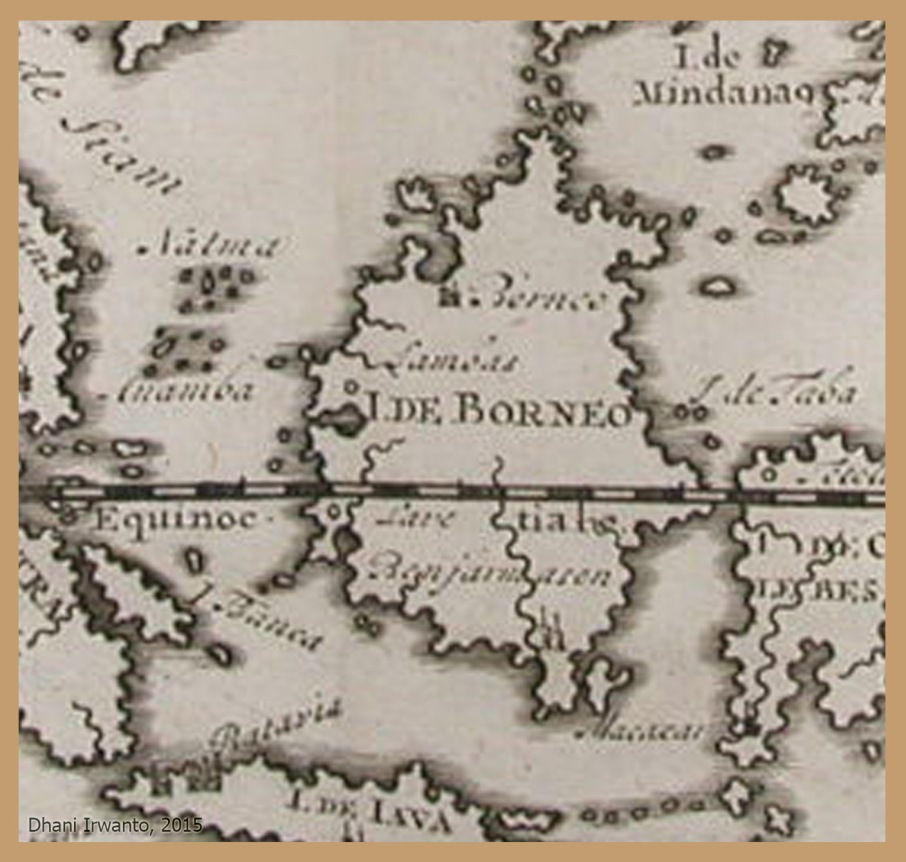

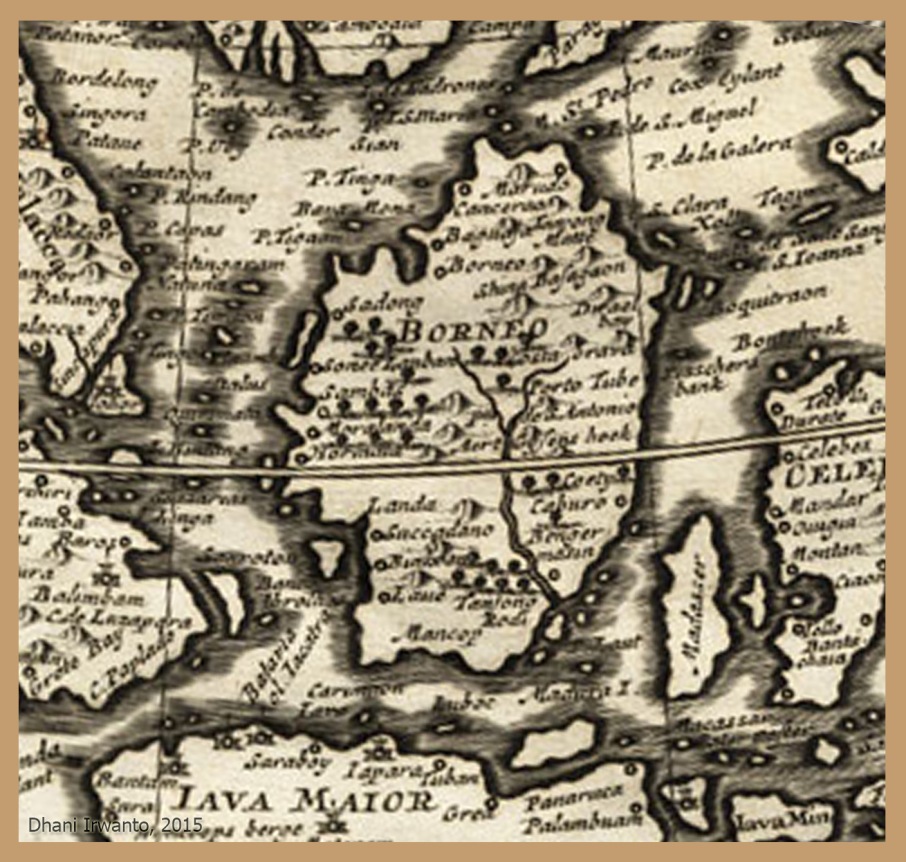

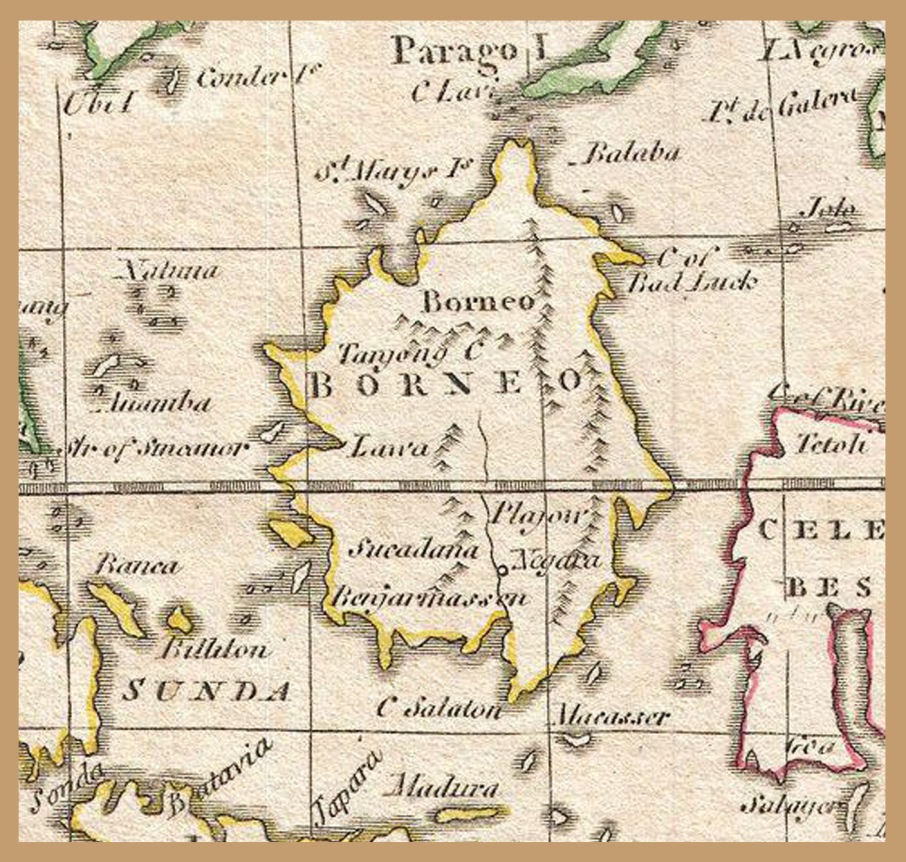

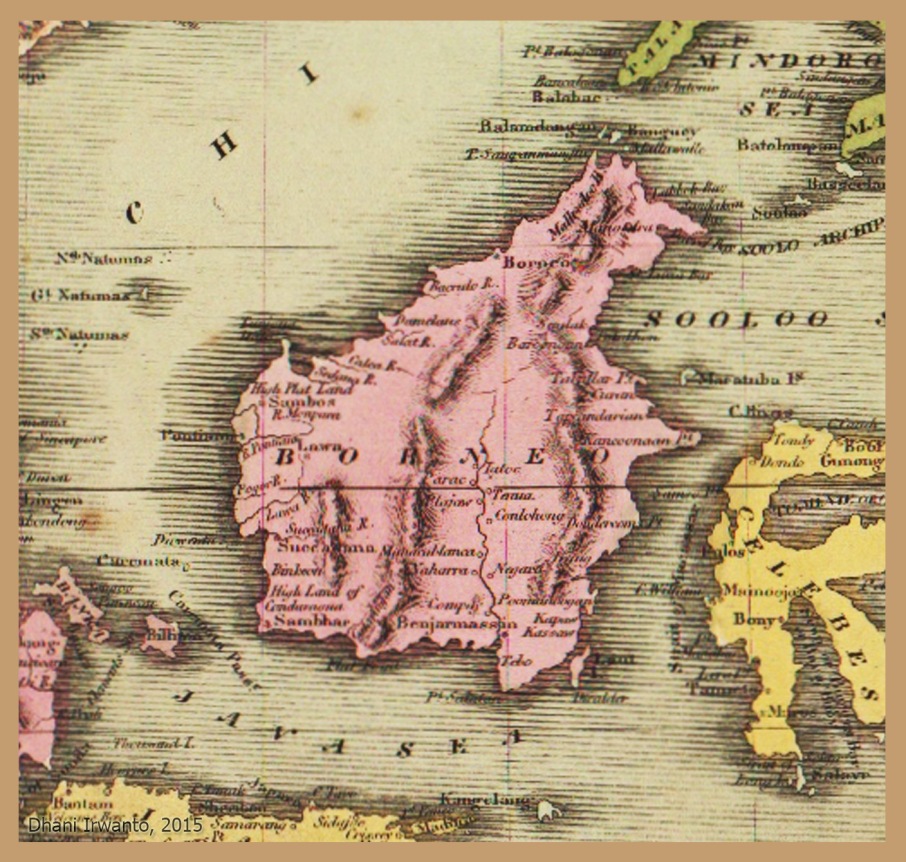

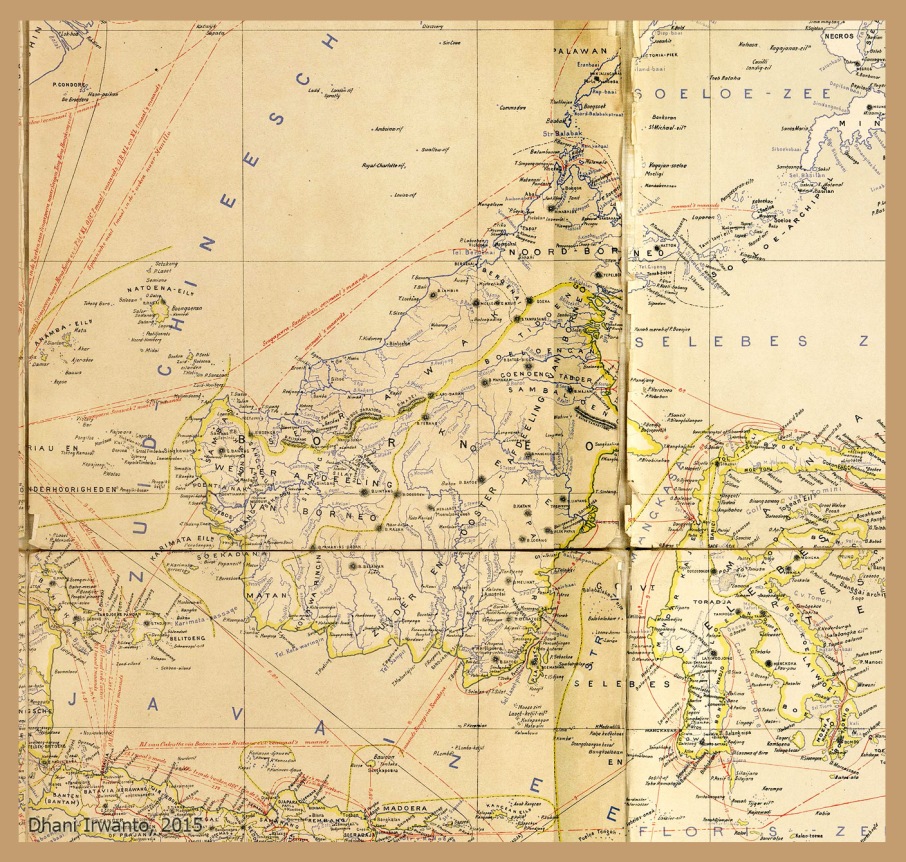

The maps below show the development of Kalimantan maps from the 16th century until the 19th, starting from the map of

Abraham Ortelius, which was the first modern atlas. The Ptolemy’s map of Taprobana is also included. We can see from these

maps that the island of Kalimantan took its real map shape just in the middle of 19th century.

The cartographers of these maps should have known that Kalimantan was actually Taprobana, visible in the great similarities

of the geographic names, layout, locations, features and descriptions of the island and its surroundings among Ptolemy’s and

their maps.

Figure 21. Ptolemy, Taprobana, 150 AD

Figure 22. Abraham Ortelius, 1570 AD

Figure 23. Abraham Ortelius, 1572 AD

Figure 24. Petrus Plancius, 1594 AD

Figure 25. Petrus Plancius, 1598 AD

Figure 26. Hondius Jodocus, 1606 AD

Figure 27. Petrus Bertius, 1616 AD

Figure 28. Gerard Mercator, 1619 AD

Figure 29. Bertius, 1627 AD

Figure 30. Ioão Teixeira, 1630 AD

Figure 31. Johannes Cloppenburgh, 1632 AD

Figure 32. Joan Janssonius, 1638 AD

Figure 33. Willem Blaeu, 1650 AD

Figure 34. Frederik de Wit, 1662 AD

Figure 35. Pierre Duval, 1680 AD

Figure 36. Alain Manesson Mallet, 1683 AD

Figure 37. Giovanni Giacomo De Rossi, 1687 AD

Figure 38. Robert Morden, 1688 AD

Figure 39. Vincenzo Maria Coronelli, 1689 AD

Figure 40. Bowrey, 1701 AD

Figure 41. Pieter Vander, 1706 AD

Figure 42. Ioachim Ottens, 1710 AD

Figure 43. John Senex, 1721 AD

Figure 44. Nicholas de Fer and J Robbe, 1721 AD

Figure 45. Chevigny, 1723 AD

Figure 46. Pierre Vander, 1725 AD

Figure 47. Herman Moll, 1726 AD

Figure 48. Christoph Homanno, 1730 AD

Figure 49. Isaac Tirion, 1740 AD

Figure 50. Nicolaus Bellin, 1747 AD

Figure 51. Robert de Vaugondy, 1762 AD

Figure 52. Thomas Salmon, 1766 AD

Figure 53. M Bonne, 1770 AD

Figure 54. M Bonne, 1771 AD

Figure 55. Antonio Zatta, 1776 AD

Figure 56. Thomas Jefferys, 1778 AD

Figure 57. M Bonne, 1780 AD

Figure 58. Clement Cruttwell, 1799 AD

Figure 59. John Cary, 1801 AD

Figure 60. Ambrosse Tardieu, 1810 AD

Figure 61. Pinkerton, 1818 AD

Figure 62. David H Burr, 1835 AD

Figure 63. Tallis, 1851 AD

Figure 64. Joseph Hutchins Colton, 1855 AD

Figure 65. JH de Bussy, 1893 AD

Figure 66. Richard Andree, 1895 AD

Geographic Names Identification

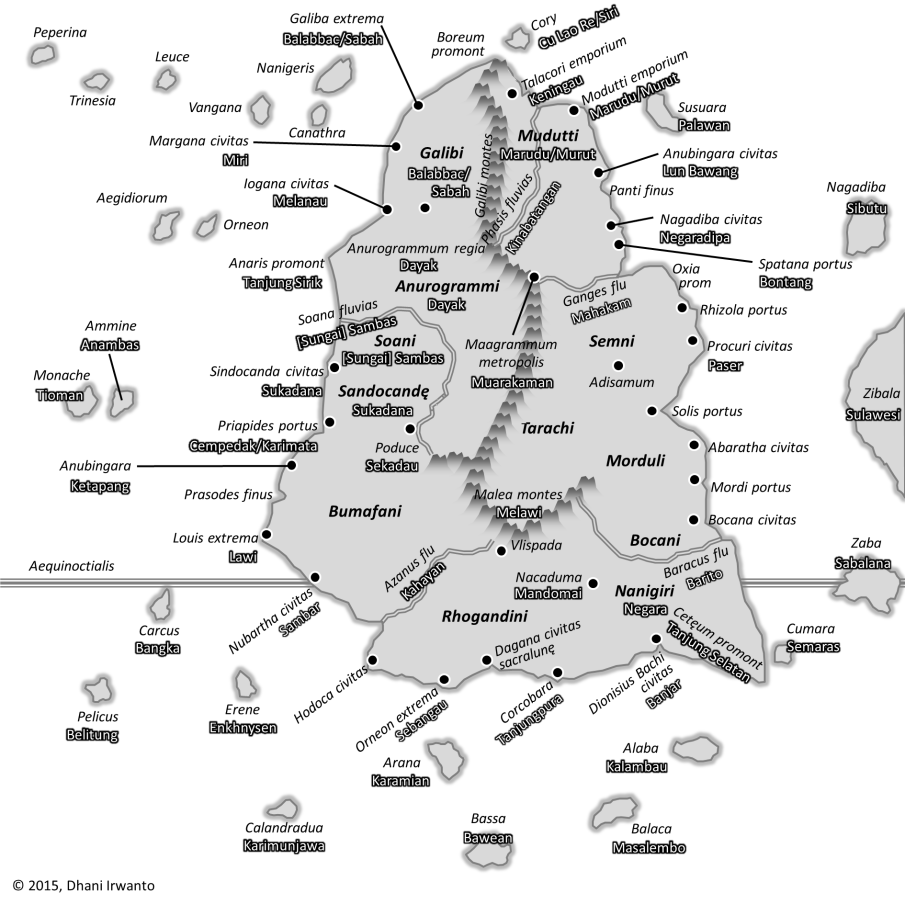

The author identifies the geographic names and locations as mentioned by Ptolemy by correlating with those in the old maps

and their modern names. Compass was not invented in the Ptolemy’s time so that the map has very low quality in terms of

scale, orientation and geographic locations. Below are the identified names. We can see that numerous names as well as their

locations are in close resemblance with those of Ptolemy’s. These are the so many proofs that Taprobana is actually

Kalimantan.

- Cetęum, promontorium → (Cotan, Catalan, Satalang, Salaton, Salatan) → Tanjung Selatan

“Tanjung” means “cape”, “promontory” or “peninsula”. Tanjung Selatan is a significant promontory located at the southeastern

part of Kalimantan.

- Nanigiri, region → (Nagara, Nagarra) → Negara

Negara was a known place name and frequently mentioned in the old maps, now a village and a river name in South Kalimantan

Province.

- Baracus, fluvius → Barito River

Some maps show Barito River as Banjar River, Banjarmasin River or misplaced as Sukadana River.

- Nacaduma, place → Mandoemai → Mandomai

Mandoemai is mentioned on the 1896 Dutch map. Mandomai is now a village in the region of Kapuas Barat Subdistrict, Kapuas Regency, Central Kalimantan Province.

- Bachi, civitas → (Paco, Bancy, Biajo, Bander, Banjar) → Banjar

Banjar is an ethnic group in southern Kalimantan and formed a kingdom of Banjarmasin from 1520 to 1860. Banjarmasin is now a

capital city of South Kalimantan Province. Some maps show Banjarmasin as Bandarmassin, Bendermassin, Bendermaβin,

Bandermachri, Bendarmafsin, Bindermasin, Baniarmafseen, Brandermassin, Banjarmassen, Banjar Massin or Banjarmaffen. Odoric of Pordenone mentioned it as Thalamasyn.

Banjar people were travellers; some of them had travelled to many places in the archipelago and set up pockets of

settlement. Megasthenes described Taprobana was inhabited by Prachii colonists, this could be the Banjar people.

- Corcobara, place → (Tamiampura, Taiampura, Taiapura, Taiaopura, Taiaopuro, Tanjapura) → Tanjungpura

Tanjungpura is a name of an ancient kingdom. Based on the old maps, its location was not static but mostly at the south and

southwest coast of Kalimantan.

- Orneon, extrema → (Simanauw) → Sebangau

“Orneo”, “ornis” and “ornêon” in Latin mean “bird”, “fowl” or “heron”. “Bangau” in local language means “hern”, “heron”,

“stork” or “egret”. Sebangau is now the name of a river and a bay at the southern coast of Kalimantan.

- Azanus, fluvius → Kayan, Kahayan River

There are several rivers with the name of Kayan (or Kahayan), in western, southern and eastern Kalimantan. Kayan is also the

name of several Dayak tribes. Azanus River is probably the Kahayan River in Central Kalimantan.

The Periplus Maris Erythraei indicates that the southern part of the

region trends gradually toward the west, and almost touches the shore of Azania (or Azanus).

- Louis, extrema → (Lao, Lave, Laue, Lava, Laua, Lawa) → Lawi, Lawai

Lawi or Lawai is an ancient city in the Ketapang Regency, West Kalimantan Province. The name is frequently mentioned on the

old maps but the exact location is controverted. Tomé Pires, a Portuguese explorer, described it as an area rich of

diamonds, four-day shipping distance from Tanjompure (Tanjungpura). Lawi is also the name of a river, a tributary of Kayan

River. Lawi is sometimes associated with Melawi, a regency in West Kalimantan Province.

- Nubartha, civitas → (Sambuer, Sambaur, Sambor, Sobar, Sambar, Sambahar, Sambbae, Samban) → Tanjung Sambar

Tanjung Sambar is a cape in the Muara Kandawangan National Park.

- Malea, mons → (Melahoei, Melawai) → Melawi

Melawi is the name of a regency in West Kalimantan Province, also the name of a river, located and has its headwaters on the

Schwaner-Muller, a mountain range with highest peaks in Kalimantan.

- Anubingara, place → (Matan, Mattan, Ketapan) → Ketapang

Ketapang is the oldest town in the western Kalimantan, was once the center of the kingdom of Tanjungpura situated at Matan. Ketapang is the capital of the Ketapang Regency, West Kalimantan Province.

- Priapides, portus → (Tamaratas, Tamaratos, Tamarates, Tameorato, Iamanatos, Hormata, Carimata) → Cempedak, Karimata

Cempedak is now the names of the two islands, off the coast of the port Siduk, Sukadana. Tamaratos and Hormata are frequently mentioned in the old maps, these are probably the modern town of Ketapang. Karimata is now the name of an island off the coast of Ketapang and a strait separating Kalimantan and Sumatera.

- Sindocanda, civitas; Sandocandę, region → (Succadano, Succaduno, Succudana, Succadana, Socadana, Sucadana) → Sukadana

Sukadana is frequently mentioned in the old maps, it was an ancient kingdom with its products are diamonds and iron.

Sukadana is now the capital city of North Kayong Regency, West Kalimantan Province.

- Poduce, place → (Landa, Salimbau) → Sekadau

Landa is frequently mentioned in the old maps, this is probably Sekadau located at the bank of Kapuas River. Sekadau is now

the names of a regency and also its capital, in West Kalimantan Province.

- Soana, fluvius; Soani, region → (Sonee, Senar, Soné, Sone, Sona, Soengi) → [Sungai] Sambas

The above names are found on the 18th and 19th century maps indicating the three rivers (or places) around the Main Sambas

River, literary mean “river” (“sungai”). These are written as Sone Sambas, Sone Luban and Sone Napor, probably the closely

neighboured Sambas Kecil, Teberau and Subah Rivers. Sambas was a kingdom from before 14th century to 1950 AD, now the

capital city of Sambas Regency in West Kalimantan Province.

- Anaris, promontorium → (Sisar, Soric, Siric) → Tanjung Sirik

Tanjung Sirik is a cape located in Sarikei Division, Sarawak

- Anurogrammum, place, Anurogrammi, region → Dayak people

Anurogrammum is in close resemblance to Anurognathus, a genus of small pterosaur. The indigenous Dayak people are hornbill admirers, have many myths and

legends in which hornbills are envoys of the gods with the task of conveying divine messages. The Anurogrammum is allegedly meant “hornbill admirer”, ie the Dayak people.

- Iogana, civitas → (Malano, Malona, Melanoege) → Melanau

Melanau people are an ethnic group native to Sarawak, the fifth largest group (after Iban, Chinese, Malays and Bidayuh), but

forms a large part of Sarawak’s political sphere. The Melanau are considered among the earliest settlers in Sarawak, at

first settled in scattered communities along the main tributaries of the Rajang River in Central Sarawak.

- Margana, civitas → Miri

Miri town is named after a minority ethnic group called “Jatti Meirek” or simply “Mirek”, or “Miriek”. This ethnic group is

the earliest settlers in the region of Miri Division, Sarawak.

- Galiba, extrema; Galibi, region; Galibi, montres → (Balaba, Balabac) → Balabac

Balabac is the southern-most island of the Palawan province in the Philippines, only about 50 kilometres north from Sabah,

Malaysia, across the Balabac Strait. The Molbogs, which is also referred to as Molebugan or Molebuganon are concentrated in

the island. The Molbogs allegedly migrated from North Borneo, related to the Tidung or Tirum people, an indigenous group

found in the northeast coast of Sabah since they have similar dialect and socio-cultural practices.

The names of Sabah, Balambangan Island and Teluk Labuk might also be derived from the same name.

- Talakori, emporium → (Cancirao, Cancyra, Canciaro, Cancerao, Cancorao, Cancirau) → Keningau

This place is frequently mentioned in the 17th- and 18th-century maps. The exact place is not known, possibly Keningau, a

district in the Interior Division, Sabah. It is the oldest and largest town in the interior part of Sabah. During the

British colonial era, Keningau was one of the most important administrative centres in British North Borneo.

- Modutti, emporium; Mudutti, region → (Marudo, Malloodoo) → Marudu or Murut people