By Dhani Irwanto, 16 January 2017

The Austronesian language family stretches halfway around the world, covering a wide geographic area from Madagascar to Easter Island, and from Taiwan and Hawai to New Zealand. The family includes most of the languages spoken on the islands of the Pacific with the exception of the indigenous Papuan and Australian languages.

Austronesian languages are spoken in Brunei, Cambodia, Chile, China, Cook Islands, East Timor, Fiji, French Polynesia, Guam, Indonesia, Kiribati, Madagascar, Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Mayotte, Micronesia, Myanmar, Nauru, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Niue, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Suriname, Taiwan, Thailand, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, USA, Vanuatu, Vietnam, Wallis and Futuna. The total number of speakers of Austronesian languages is about 386 million people, making it the fifth-largest language family by number of speakers, behind only the Indo-European, Sino-Tibetan, Niger-Congo and Afroasiatic languages.

Figure 1 – Spread of Austronesian language family

The existence of the Austronesian language family was first discovered in the 17th century when Polynesian words were compared to words in Malay. Otto Dempwolff was the first researcher to extensively explore Austronesian languages using the comparative method. Another German, Wilhelm Schmidt, coined the German word austronesisch which comes from Latin auster (south wind) and Greek nêsos (island). The name Austronesian was formed from the same roots. The family is aptly named, as the vast majority of Austronesian languages are spoken on islands: only a few languages are indigenous to mainland Asia.

With 1268 languages, Austronesian is one of the largest and the most geographically far spread language families of the world. Austronesian and Niger-Congo are the two largest language families in the world, each having roughly one-fifth of the total languages counted in the world. The geographical span of Austronesian languages was the largest of any language family before the spread of Indo-European in the colonial period, ranging from Madagascar off the southeastern coast of Africa to Easter Island in the eastern Pacific.

Despite extensive research into Austronesian languages, their origin and early history remain a matter of debate. Some scholars propose that the ancestral Proto-Austronesian language originated in Taiwan (Formosa), while other linguists believe that it originated in the islands of Indonesia.

The Austronesian language family is usually divided into two branches: Formosan and Malayo-Polynesian, with the latter is by far the largest of the two. Malayo-Polynesian is traditionally divided into two main sub-branches: Western and Central-Eastern.

The Western sub-branch includes 531 languages spoken in Madagascar, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, parts of Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, Micronesia (Chamorro and Palauan, represents over 300 million speakers and includes such widely spoken languages as Javanese, Malay, and Tagalog. The Central-Eastern sub-branch, sometimes referred to as Oceanic, contains around 706 languages spoken in most of New Guinea and throughout the islands of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia but excluding the aboriginal Australian and Papuan languages, represents only under 2 million speakers.

The seven largest Austronesian speakers are: Javanese (~100 million), Filipino/Tagalog (~70 million native, ~100 million total), Malay (Malaysian/Indonesian) (~45 million native, ~250 million total), Sundanese (~39 million), Cebuano (~19 million native, ~30 million total), Malagasy (~17 million) and Madurese (~14 million). Twenty or so Austronesian languages are official in their respective countries.

Javanese

Javanese language is a member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family. Its closest relatives are Malay, Sundanese, Madurese and Balinese languages. It is the most spoken Austronesian language, and the tenth largest language by native speakers in the world, and the largest language without official status in the world. Javanese is considered to be one of the world’s classical languages, with a literary tradition that goes back over a thousand years.

Javanese is the native language of more than 100 million people. Javanese is spoken by over 75 million people in the central and eastern parts of the island of Java. There are also pockets of Javanese speakers in the northern coast of western Java, mainly around Banten and Cirebon. Approximately 7.5 million Javanese speakers reside on the island of Sumatera in the North Sumatera Utara and Lampung (southern Sumatera) provinces. It is also spoken in Malaysia (concentrated in the states of Selangor and Johor), in the Netherlands and in Singapore. In addition, there are Javanese settlements in Papua, Sulawesi, Maluku, Kalimantan and Sumatera. Javanese is also spoken in the former Dutch colony of Surinam and New Caledonia.

Figure 2 – Spread of Javanese language in Java

(Source: Ethnologue, Languages of the World, Javanese)

(Source: Ethnologue, Languages of the World, Javanese)

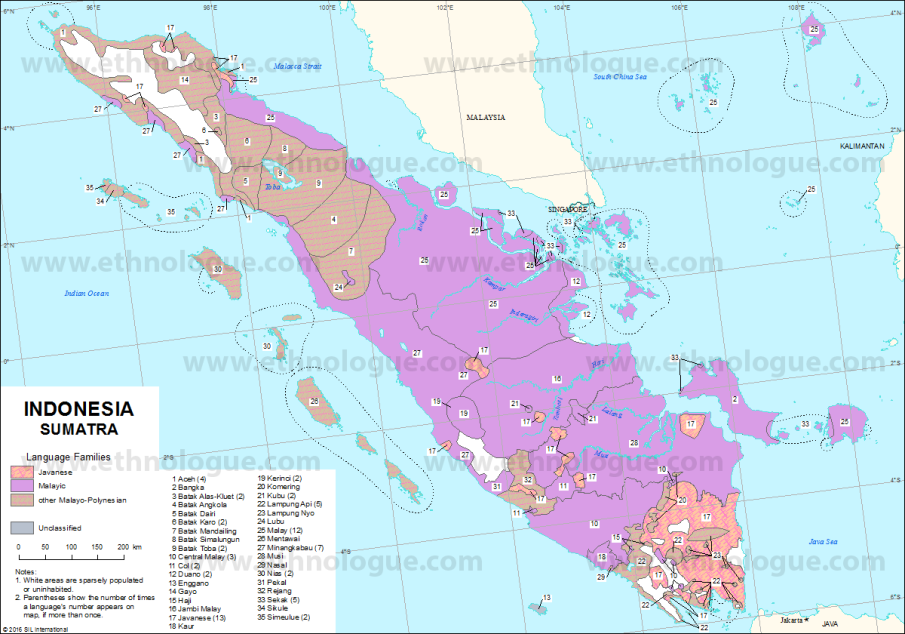

Figure 3 – Spread of Javanese language in Sumatera

(Source: Ethnologue, Languages of the World, Javanese)

(Source: Ethnologue, Languages of the World, Javanese)

Javanese is one of the Austronesian languages, but it is not particularly close to other languages and is difficult to classify. Most speakers of Javanese also speak Indonesian, the standardized form of Malay spoken in Indonesia, for official and commercial purposes as well as a means to communicate with non-Javanese-speaking Indonesians.

Scholars recognize four stages in the development of Javanese language: Old Javanese (up to the 13th century), Middle Javanese (up to the 15th century), New Javanese (up to the 19th century), and Modern Javanese (present-day Javanese).

The Javanese language can be traced back to at least 450 CE via the Sanskrit Tarumanegara inscription, although accounts regarding the origins of the Javanese people and their language are largely speculative. The oldest attestation of a work composed entirely in Javanese is the Sukabumi inscription located in the district of Pare in the Kediri regency of East Java, a work that dates from 804 CE, which is a copy of the original, dated 120 years earlier. The 8th and 9th centuries marked the beginning of the Javanese literary tradition, punctuated by the Buddhist treatise Sang Hyang Kamahayanikan and a Javanese rendition of the Sanskrit epic Ramayana. In 1293, the eastward expansion of the Hindu-Buddhist-Eastern Javanese empire known as Majapahit resulted in the spread of the Javanese language and writing system to Bali and Madura. Around the middle of the 14th century, Javanese replaced Balinese as the language of government and literature in Bali.

The Majapahit Empire saw the rise of Middle Javanese as effectively a new language, intermediate between Old and New Javanese, though Middle Javanese is similar enough to New Javanese to be understood by anyone who is well acquainted with current literary Javanese.

The Majapahit empire fell to Islamic forces around the turn of the 16th century, signaling the end of the Hindu Javanese empire. This ushered in the rise of the Islamic Javanese empire known as Mataram Sultanate, which was originally a vassal state of Majapahit. The 16th century saw the emergence of the New Javanese language. As the empire conquered a number of Sundanese areas of western Java, the Javanese language and culture spread westward. In its wake, Javanese became the dominant language, absorbing and heavily influencing languages like Sundanese, as was the case with Balinese in the 14th century. It was also the court language in Palembang, South Sumatera, until the palace was sacked by the Dutch in the late 18th century.

In later years, contact with Dutch colonizers and other Indonesian ethnic groups influenced the character of the language in numerous ways, the most notable being the influx of foreign loanwords.

Tagalog

Tagalog language is a member of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family with more than 70 million speakers (28 million speakers as first language) in the Philippines, particularly in Manila, central and southern parts of Luzon, and also on the islands of Lubang, Marinduque, and the northern and eastern parts of Mindoro. Being Malayo-Polynesian, it is related to other Austronesian languages, such as Javanese, Malay (Indonesian and Malaysian), Sundanese, Cebuano, Malagasy and Madurese. It is the second most spoken Austronesian language after Javanese and before Malay. Tagalog speakers can also be found in many other countries, including Canada, Guam, Midway Islands, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom and USA.

Figure 4 – Spread of Tagalog language

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The first written record of Tagalog is the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, which dates to 900 CE and exhibits fragments of the language along with Sanskrit, Malay, Javanese and Old Tagalog. The first known complete book to be written in Tagalog is the Doctrina Christiana (Christian Doctrine), printed in 1593.

Malay

Malay language, spoken in Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, parts of Thailand and southern Philippines, is a major language of the Austronesian language family. Over a period of two millennia, from a form that probably consisted of only 157 original words, Malay has undergone various stages of development that derived from different layers of foreign influences through international trade, religious expansion, colonization and developments of new socio-political trends. Within Austronesian, Malay language is part of a cluster of numerous closely related forms of speech known as the Malayan languages, which were spread across Malay Peninsula and the archipelago by Malay traders from Sumatera.

Modern Malay language has various official names. In Singapore and Brunei it is called Bahasa Melayu (Malay language); in Malaysia, Bahasa Malaysia (Malaysian language); and in Indonesia, Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian language); where the latter contributes about 60% of the total of all speakers. However, in areas of central to southern Sumatera where the language is indigenous, Indonesians refer to it as Bahasa Melayu and consider it one of their regional languages.

Figure 5 – Spread of Malay language

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The oldest form of Malay language, the Ancient Malay or Proto-Malay language, was descended from Proto-Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the earliest Austronesian settlers in Southeast Asia, that derived from Proto-Austronesian which began to break up by at least 2000 BCE. Proto-Malay language was spoken in Kalimantan at least by 1000 BCE and was, it has been argued, the ancestral language of all subsequent Malay dialects. Linguists generally agree that the homeland of the Malayic-Dayak languages is in Kalimantan, based on its geographic spread in the interior, its variations that are not due to contact-induced change, and its sometimes conservative character. Around the beginning of the first millennium, Malayic speakers had established settlements in the coastal regions of modern-day South Central Vietnam, Tambelan, Riau Islands, Sumatera, Malay Peninsula, Kalimantan, Luzon, Maluku Islands, Bangka-Belitung Islands, and Java.

With the penetration and proliferation of Dravidian vocabulary and the influence of major Indian religions, Ancient Malay evolved into the Old Malay language. The oldest uncontroversial specimen of Old Malay is the 7th-century-CE Sojomerto inscription from Central Java, Kedukan Bukit inscription from South Sumatera and several other inscriptions dating from the 7th to 10th centuries discovered in Sumatera, Malay Peninsula, western Java, other islands in the archipelago, and Luzon.

Malay evolved extensively into Classical Malay through the gradual influx of numerous Arabic and Persian vocabulary, when Islam made its way to the region. Earliest instances of Arabic lexicons incorporated in the pre-classical Malay written in Kawi was found in the Minyetujoh inscription dated 1380 CE from Aceh. Pre-Classical Malay took on a more radical form as attested in the 1303 CE Terengganu inscription and the 1468 CE Pengkalan Kempas inscription from Malay Peninsula. Initially, Classical Malay was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the Malay kingdoms of Southeast Asia. The language spread through interethnic contact and trade across the archipelago as far as the Philippines. This contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay (melayu pasar, market Malay). It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups that do not have a language in common.

From 19th to 20th century, Malay language evolved progressively through a significant grammatical improvements and lexical enrichment into a modern language with more than 800,000 phrases in various disciplines.

Role of Austronesian-speaking People around the World

Austronesian-speaking people were a maritime people with considerable navigational skills. This maritime heritage has allowed the Austronesian-speaking people left their cultural and material marks in the regions of the world and it is not unreasonable to assume that they can reach other continents, including Americas. Archaeology, transfer of crops and material culture, and historical records can all contribute to explore Austronesian-speaking people relationships with the world communities. Genetic evidence increasingly has strengthened the belief of the existence of these relationships and supports the notion of cultural transfer that have been there before. Blow-guns, backstrap looms, bark-cloth, paper, coconuts, sweet potatoes, bottle-gourds, sailing rafts, are striking examples of technology spread by Austronesian contacts (Roger Blench, 2014).

Genomic analysis of cultivated coconut (Cocos nucifera) has shed light on the movements of Austronesian-speaking people. By examining 10 microsatelite loci, researchers found that there are 2 genetically distinct subpopulations of coconut – one originating in the Indian Ocean, the other in the Pacific Ocean. However, there is evidence of admixture, the transfer of genetic material, between the two populations. Given that coconuts are ideally suited for ocean dispersal, it seems possible that individuals from one population could have floated to the other. However, the locations of the admixture events are limited to Madagascar and coastal east Africa and exclude the Seychelles. This pattern coincides with the known trade routes of Austronesian sailors. Additionally, there is a genetically distinct subpopulation of coconut on the eastern coast of South America which has undergone a genetic bottleneck resulting from a founder effect; however, its ancestral population is the pacific coconut, which suggests that Austronesian-speaking people may have sailed as far east as the Americas.

Figure 6 – Locations of rock arts with boat paintings

Archaeologists have revealed ample evidence of the active maritime networks in the Southeast Asian region that existed from at least 5,000 years ago, at the beginning of the Austronesian migration that spread throughout all of insular Southeast Asia and most of the Pacific (Bellwood, 1985, 1991, 1995; Bellwood and Dizon, 2005; Horridge, 1995; Reid, 1988; Ronquillo, 1998; Scott, 1994; Solheim, 1988, 2006). As pointed out by linguists, archaeologists and anthropologists, shared cultural traits such as language, agriculture, animal husbandry and pottery-making are evidence of the Austronesian maritime connection. Likewise a boat building tradition emerged out of Southeast Asian islands but scarcely addressed in archaeology and history subjects.

Similarities between boat-building technology in the regions of Austronesian-speaking people and in the Indian Ocean about 5,000 years ago were observed. Wooden boards added on the canoe hulls and sewn-plank boats spread across the archipelago were also observed on the boats in Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Indus River Valley. However, Horridge (2006) claimed that it is not appropriate to correlate them seeing that the Austronesian speaking people spread over the archipelago long before they were influenced by boat-building technology in the Indian Ocean or even Egypt. He shows that the Austronesian boats were developed using a triangular-shaped sail since about 200 BCE demonstrated by the spread of bronze kettle which is one of the artifacts of the Dong Son culture, but this sail type was developed in the Indian Ocean more recently about 200 CE and was adopted by the Portuguese sailors a thousand years later.

Austronesian boats on its development have unique characteristics with a triangular sail and single outrigger. The outrigger is made of bamboo trunks with transverse connectors at the top of the hull, while the triangular sail is formed using bamboo sticks supported by a slanting mast (Horridge, 2006).

Cloves and cinnamon were allegedly trade commodities brought by Austronesian speaking sailors towards India and Sri Lanka, and perhaps also towards the east coast of Africa by outrigged boats. They left trails of influences such as boat design, boat building techniques, outriggers, fishing techniques and so on as evidenced in the Greek literature (Christie, 1957 in Horridge, 2006). Hornel (1928 in Horridge, 2006) supported this argument that the boat shape in Bantu tribe in Victoria Nyanza, Uganda in East Africa is similar to those in Indonesia.

***

No comments:

Post a Comment